The Bagpipe Society

The Gaida in Greece

Fall 1992. I was 17 and walking down the central square of Thessaloniki (map 1: 1), the second largest city after the capital of Greece Athens (map 1: 2). I was going to my Sunday math class as I was preparing for my university entrance exams, and my days were rather dull studying hard, as was that windy autumn day. While reaching my final destination, I had my first ear- contact with a sound which would haunt me from that day on for several years. There, in the centre of the square, was an old person playing, what I believed to be at that time, a bagpipe. In my little musical universe, bagpipes existed only in Scotland, so this experience was stored as my first real encounter with a Scottish bagpipe. I did not know much, back then, growing up in the grey urban environment of Thessaloniki.

In the following years I came across this instrument again on some rare occasions. Once a gypsy street musician played it at the bus stop whilst begging for money and on another occasion, at a concert, a bagpipe appeared only in one song. I heard it again in a folkrock song from 1971 listen at https://bit.ly/Gaida1 and another from 1996 https://bit.ly/Gaida2 where the bagpipe made a small appearance, adding some colour to the main tune. At some point a strange bagpipe appeared in a movie from 1963 where ancient Greeks were dancing to a bagpipe tune https://bit.ly/Gaida3 and it another movie a dramatic tune was heard as the hero “Astrapogiannos” was dying. https://bit.ly/Gaida4

This was all I got to hear from the instrument until 2005. It was not much, but I always loved to hear these small parts whenever media played them. It always blew me away.

At some point I went to a music school to ask if there were lessons for the bagpipe. I was confronted with a no. The only information I managed to get was that it was a gaida and that it was actually played in the Northeastern part of Greece. A place called Evros, bordering Turkey in the east and Bulgaria in the northwest. An unpopular place for most Greeks.

In 2005, in my thirties, my pursuit for a job opportunity brought me to Alexandroupolis (map 1: 2), the capital of the prefecture of Evros. So, there I was, in Evros where no Greek wanted to end up and the last thing I had on my mind were bagpipes. Living in a new little city wasn’t really exciting. One day, while strolling around the city, a leaflet drew my attention informing the passersby about gaida classes. And a little light turned on. Some days later, I visited the place and after I was accepted as a student, meaning that I was willing to pay.

Then I was urged to get my gaida ready for the lesson. That was an issue of course as I didn’t have one! I was given two solutions. Either travel to Bulgaria to buy one there or go to the villages of the Northern Evros Region to find a maker.

The Internet was not very helpful at that time. I found it easier to travel to Didymoteicho, the de facto capital of the northen Evros region, a two hours’ drive from Alexandroupolis back then. By asking around I was given the number of a maker, Mr Paschalis Chrisidis. I called him and was invited for a visit.

Unfortunately, I didn’t manage to get a gaida from him. As he confessed, he was too old and he was not making instruments anymore. What I got though was an amazing evening with an old man telling stories about his youth as a shepherd, the Second World War, the following civil war and all the ugly things connected with them and a lot of other things which deserve to be forgotten in oblivion. We drunk a bit of his own sweet wine and then he played his gaida.

And so, after 13 years from my first encounter, I finally heard somebody play the gaida for half an hour nonstop. And somewhere there, magic happened!

Let’s round up the situation concerning learning the gaida in the urban environment of the cities in Greece up to 2005: Almost no media coverage of the instrument, almost no recordings to buy and listen to relevant music, almost nobody teaching the instrument, almost no makers. And the worst of all - no information. I was lucky to be at the right spot at the right time in 2005. The older generation started to realize that this knowledge had to be passed over to the newer generation. So, little by little. many young gaida players appeared. I will not go in detail about the time prior to 2005. A lot of important work has been done by ethnomusicologist, Haris Sarris, who worked in that region from 1996 -2004 [1] I was one of the few people trying to learn the instrument at that time. Unfortunately, I ended up buying a gaida from Bulgaria, which sounded rather different from what I expected. It was a good instrument, but it was different. There were some good makers building the Greek version of the gaida, but I was not able to track them down. I started classes with Mr Vagelis Doropoulos, from the village of Salpi in Xanthi, who was the only one teaching the gaida in structured classes at that time. After one years of practice, and much frustration, I managed to play some tunes. So, I made my way up to Didymoteicho again and paid Mr. Paschalis Christides my second visit. I was eager to show him my progress and to “steal” some tricks from him. It was a big disappointment from my side, our gaidas didn’t match in pitch and our playing styles were very different. I could keep writing for quite a long time about my journey to master the instrument, but I will keep that for another time. But let’s dive in to some facts about the presence of the gaida from ancient up to modern time in Greece. ]

Historical evidence of the gaida in the Greek speaking world

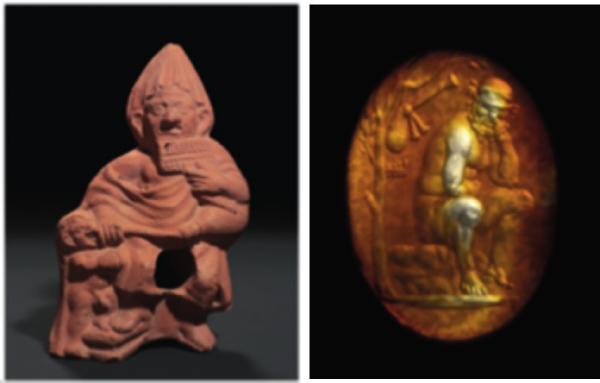

There are no known depictions of bagpipes from the classical Greek period (8th century BC – 323 BC). We can see avlos, lyra, cympal on numerous terracotta and murals but no bagpipes. The first artifacts implying its presence are from the Hellenistic period (323-146 BC) and are found in Alexandria, in what used to be the Kingdom of Ptolemeus, today’s Egypt. It is a terracotta figure of a sitting musician [2] and and a carved gem [3].

Writers from the Roman period, Gaiusuetonius Tranquillus (cAD 69 – AD 122) and Dio Chrysostom (c40 – c115 AC) mention the instrument as a cultural import from the east [4]. The first known undoubted depictions of a gaida on the geographical borders of modern Greece comes from murals located at the Varlaam at Meteora (map 1: 5) [4] and Stavronikita [5] at the Holy Mountain (map 1: 6) monasteries. Both were painted by Theophanis Mpathas Strelizas (1500-1559) [5] from Crete.

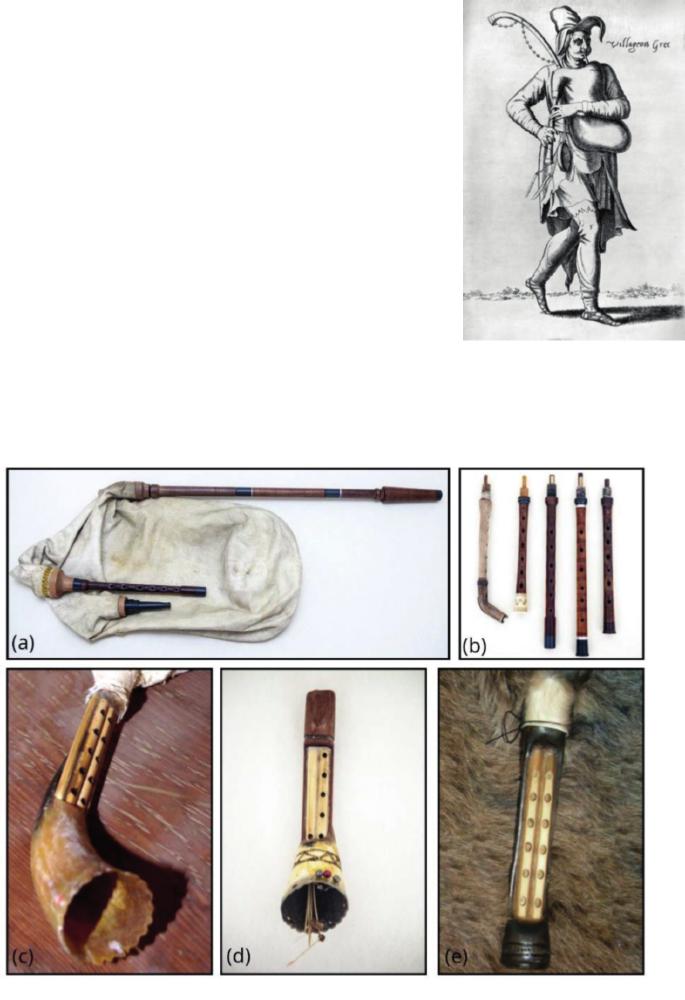

Furthermore, from the same period (1567) comes a work from Nicolas de Nicolay Dauphinoys [6] titled “Les navigations, peregninations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie” with the name Villageois Grec (Greek Villager). It is notable that the name gaida is not mentioned anywhere.

Bagpipes common in Greece and their basic terminology

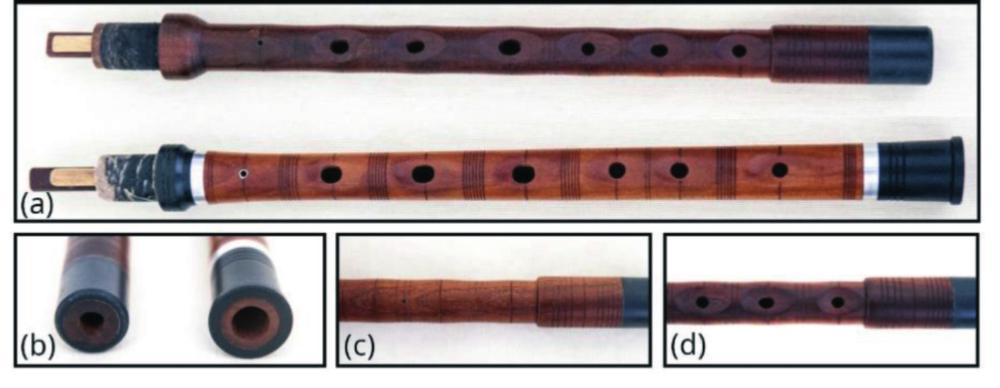

The Greek term for the bagpipe is askaulos. Askos (Ασκός) is the Greek equivalent for the bag, while aylos (Αυλός) is the pipe. I will focus on the bagpipes common in mainland Northern Greece which are known as gaida, or variants of this name. The gaida is a single reeded pipe with a drone (plate 1: a,b) Furthermore, a different variant of the askaulos is encountered on the islands in Southern Greece where it is called tsambouna, (τσαμπούνα) in the Cyclades (plate 1: c,d) and askomantoura (ασκομαντούρα) on Crete (plate 1:e). This askaulos is a single reeded double chanter bagpipe without a drone.

A third type of askaulos is the Tulum, also called aggeion, whch literally means ‘vessel’. It is played by the Pontic Greeks who were deported from the Black Sea region between in 1922 after their genocide. They settled all over Greece bringing their own music, repertoire and instruments.

The bagpiper is usually called gaidatzis (γκάιντατζής) in the North, and tsambunieris in the south. Festivities in villages are called panigiri (πανηγύρι), and smaller private parties are called glenti (γλέντι) which are held in small taverns called kafenio (καφενείο) or at private homes. As I mentioned earlier, I will focus on the gaida, which I play and am familiar with.

The gaida consists of a chanter and a drone, which is longer. The sound is produced by a single reed made from cane, or branches of the black elder (Sambucus nigra). The latter has a spongy tissue inside and can be easily hollowed out. Nowadays, modern materials are used which are more resilient to moisture but don’t produce the fuller sound of the traditional materials. The gaida has 7 holes plus one on the back. The middle hole, the fourth counted from the base of the chanter, is the tonic. In the case of the common gaida it is tuned in standard A440. When it comes to the Evros gaida the tuning is usually around Bb.

Furthermore, the chanter is shorter (plate 2: a) and the bore at the base is cylindrical and not conical, as in the common gaida (plate 2: b). Also, there is a small tuning hole at the back, between the second and the third hole (plate 2: c,d) which is used to tune the last two holes E4 and F#4 (standard tuning). The drone is 2 octaves lower of the tonic. Great care is taken to tune the E4, so as to ensure that the drone’s third harmonic exactly matches this note. The third harmonic of the A2 (110Hz in standard tuning) is 330Hz, almost matching the 329.63 of the E4.

The E4 is the most silent note, so playing it between notes creates a notion of stops between them. In this way a staccato is achieved [7]. The bag is traditionally made by goatskin turned inside out. The hair is cut short but not removed as it absorbs the humidity while the air is blown inside the bag. In this way, the reed of the chanter and the drone stay longer in tune.

Distribution of the gaida in Northern Greece

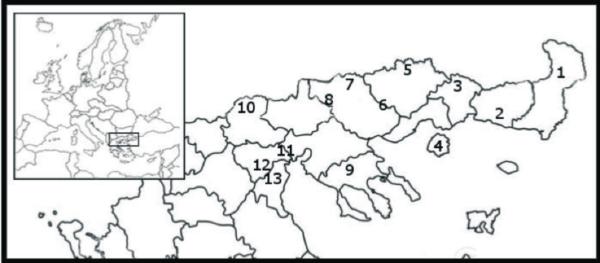

When I started learning the gaida, I was left with the impression that the Evros region was the only one where the gaida was been played, but I was wrong. Evros may be the flagship of the gaida in Greece, and from 1995 to 2004

the Thrace Research Program was conducted there, leading to new insights to this area’s musical heritage [1]. While travelling around the villages of Northern Greece, I discovered that the gaida used to be played throughout all the regions of Northern Greece. Unfortunately, nowadays, only some villages keep this tradition alive. These regions are shown on map 2.

In the marked group of villages prior to 1945 it was common to play the gaida in festivities. 1. Evros region 2. Rhodopi 3. Xanthi 4. Theologos, Panagia,

Potos (Thassos Island, Kavala) 5. Volakas, Granitis (Drama), 6. Kalivrisi (Drama), Mikropoli, Alistrati (Serres) 7. Agrianoi, Oreini, Xirotopos 8. Vamvakofito, Chrisochorafa (Serres), 10 Loutraki (Pella), 11. Trikala (Imathia), 12. Daskio, Rizomata (Imathia), 13. Elatochori, Milia (Pieria).

The Northern Evros region

From 2005 I travelled around the Evros region and recorded many gaidatzides. In 2015 I started my website www.gaida.gr, and soon after I started publishing videos recorded during my visits. The gaidatzides featured on my website are not professional musicians, nor did they undergo any formal music tuition. The instrument was learned by observing and listening to older players.

The instruments were usually built by the player with whatever material was handy.

My field work started in 2005 by first visiting Mr Paschalis Christides in Didymoteicho (map 3: 5). In the following years (2008-2018) I started shooting videos of the gaidatzides of Northern Evros. In 2008 I visited Papatzikis Vasilis from Vrysoula (map 3: 1) living in Alexandroupolis at that time. In 2009 Sideris Vlachos from the village of Megali Doxipara (map 3: 2). In 2011 Logaroudis Theodosis from Asvestades village (map 3: 4) and Kitsikoudis Paschalis from Patagi (map 3: 3). In 2012

Charokopides Vaitsis from the village of Patagi (map 3: 3), Christides Pachalis from Didymoteicho (map 3: 5) and Pechlivanis Ioannis from the village of Lagos (map 3: 6). In 2016 Christos Gkotsios from Soufli (map 3: 7). In 2018 a video of young people paying a tribute night visit to Pechlivanis Ioannis was filmed

[https://bit.ly/Gaida13]. Al these videos are freely available via www.gaida.gr.

The Gaida in Greece Today

Nowadays there are numerous young players. The three public musical schools of Xanthi, Komotini and Alexandroupolis included gaida lessons in their curriculum. It is indicative to notice that on the 17th of January 2022, just last year, a law was passed (KYA 7275/2022 FEK 77/b/17-1-2022) making it possible to get a music degree using the gaida as the main instrument. Furthermore, new music is made incorporating the gaida with other instruments. Many individuals, like myself, offer music lessons in person or on-line for the gaida and its repertoire.

All the material presented here can be accessed from the website www.gaida.gr/

You can contact me at info@gaida.gr, or call directly +30.6945260121. Getting to know and learn the gaida has become much easier than it was back in 1992.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Mr I Sarsakis and Mr D Sinapidis from Didymoteicho, who are members of the association of traditional instrument players “Ioannis Vatatzis” for organizing meetings with the gaidatzides. This research has been self-financed but I have to thank Mrs R Roth for her financial support and for persuading me to attend the 6th

conference of the International Bagpipe Organization (IBO) in Newcastle, March 12th 2022.

It was there that Jane Moulder, editor of Chanter magazine, published by the Bagpipe Society, proposed that I should write this article. Thanks to Mrs Vaso Michailidou and Mr Wiebe Stodel for reviewing the manuscript.

References:

- H. Sarris, “I gaida ston Evro: Mia organologiki ethnographia [The gaida bagpipe in theEv-ros region of Greek Thrace: An organological ethnography] (in greek),” Athens, 2007.

- M. A. Wardle, “Musical Instruments in the Roman world,” University of London Institute of Archaeology, London, 1981. [Online]. Available: https://bit.ly/Chanter153

- J. Boardman, Engraved gems. The Ionides collection. 1968.

- F. Anoyianakis, Greek Popular Musical Insruments. Melissa Publishing House, 1979.

- M. Catzidakis, The Cretan Painter Theofanos. The mural pauntings of the Sacret Monastery of Stavronikita [O Kritikos Zografos Theofanos. Oi Toixografies tis Ieras Monis Stavronikita] (in greek). Sacret Monastery Stavronikita - Holy Mountain, 1997.

- N. de Nicolay, Quatre premiers livres des navigations. 1567. [Online]. Available: https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbc0001.2008rosen1207/?sp=3

- H. Sarris and P. Tzevelekos, “‘Singing like the Gaida (Bagpipe)’: Investigating Relations between Singing and Instrumental Playing Techniques in Greek Thrace,” J. Interdiscip. Music Stud. , no. spring/fall, pp. 33–57, 2008

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!