The Bagpipe Society

Alfranio’s Phagotus

Instrument makers tend to be obsessive in nature. It helps, when things don’t go well in the development of an instrument, to focus on the faint possibility of there being a solution to the problem at hand, no matter the time it might take. So it must have been for Canon Alfranio in Ferrara in Italy in 1510

when he was desperate to make a name for himself by inventing a new bagpipe of such complexity as to amaze all who saw it.

And so it was for me when on my second year at West Dean College on the Easter instrument making course being tutored by Eric Moulder. I had made the decision to run away from life with a tie around my neck, to one of sawdust and machines, and I was looking for a project to learn how to research and develop woodwind instruments from historic information. And then Barry Lloyd, who was also on the course, pushed a very small image of the woodcut of the Phagotum under my nose, and that was the next 8 years of my life before me.

Canon Alfranio was an organ collector and musician living in Ferrara, and he set upon a 25 year project to create a new bagpipe. Having made some progress, he had commissioned a very detailed woodcut showing the back and front of his Phagotum, with the intention of having it included in Ottomarus Luscinius’s Musurgia published in Basle in 1518. This was a Latin edition of parts of Virdung’s book on musical instruments. But, sadly, it missed the publishing deadline and was returned to him unused.

Canon Alfranio dies sometime after 1518, and the woodcuts fall into the hands of his nephew, Theseo Ambrogio, who was the Pope’s enforcer of doctrine at this time.

Ambrogio was also a professor of linguistics, specialising in the languages of the Eastern Countries and is concerned that Christianity should be brought to the inhabitants of these “heathen” lands. At the time he was writing a book containing the main works of the bible in 20 eastern languages so that each of the 350 Jesuit priories in the world at that time could have these key texts, written in the scripts and languages of countries from Macedonia to Syria.

For reasons unknown, he decides to publish the woodcuts of his uncle’s bagpipe on page 179, and 5 pages of description on pages 21 – 26. It was not

unusual to publish unrelated information in books of the time, however random this might seem to us today.

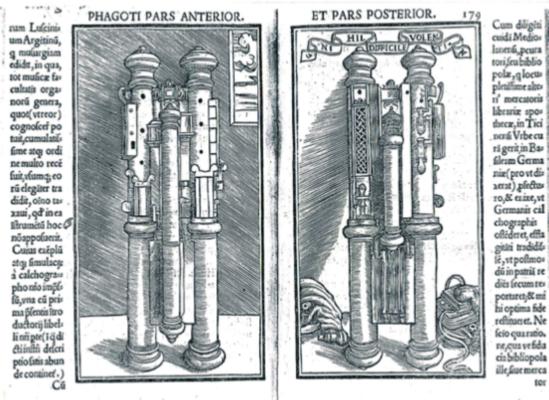

So the book, Introductio in Chaldaicam Linguam, published in 1539, gives us a wonderful woodcut and five pages of mostly useless text in Latin about the instrument. Ambrogio is unfortunately not a musician and is mostly writing florid text comparing the wonderful instrument with various Greek gods of antiquity and describing how well it was made. But he does tell us that it has two chanters, which can be switched on and off, along with one drone. And that the reeds are concealed in the lower half of the instrument with one facing down and the other facing upwards on a bent pipe to give a lower pitch.

He also tells us the height of the instrument is a “mean cubit” (that being the length of a man’s forearm) and that it is made of boxwood with silver keys.

Looking at the woodcut, you can clearly see the bag and bellows in the

“Posterior” image. The “Anterior” view shows the two chanters, with the left side being at bass pitch and the right side tenor pitch The lower halves of each side are effectively the windcaps where the reeds are located, with the air going into the bagpipe from the top of the tube in the middle of the Posterior view. The long tube in the middle of the Anterior view is the single drone.

It is also clear from the text in the book that there was more than one version of the instrument was made. One is described as only having 12 notes, whereas the one in the woodcut has 10 notes on the tenor chanter and 10 on the bass chanter. There is also a reference in the texts to an instrument/model with 22

notes in total being available. We are told the first model didn’t work at all well, and after hawking the instrument around various instrument makers in Eastern Europe in the hope of improving it. After trying instrument makers in Hungary, Germany and Serbia he ended up in Ferrara where it was finally made in to a

‘magnificant instrument" by the local woodturner and silversmith, John Baptisto Ravilio. It only took him 25 years to get a playable instrument.

To give you an idea of Ambrogio’s text in the book, here is an example of a rare useful passage describing the drone in the middle on the front of the Phagotum. He clearlydoesn’t realise it is a drone!

“Between each pillar another small sort of turned pillar is seen adjoining, rather* for the adornment and pleasing appearance of the instrument than of necessity, with its base and suitable cap, but not equal in length to the other two; nevertheless it is empty and added as a sort of connection between them. This pillar is applied with due symmetry and proportion so that, although it strikes the eye at first sight, yet does not, on account of its presence trench upon the appearance of the other two pillars and their decoration of varied graven-work nor on the holes on either side; nor does it interfere of the musician as *he plays upon them.”

And then there is:-

“Very many other hidden secrets of musical capability it has, wherewith anyone,* who like Alfranio has known how to employ them properly and systematically, will rival the tones and sounds of all instruments of music and awaken a united and pleasing concord of harmony worthy of the citizens of heaven. If that upstart Marsyas had in olden days used this Phagotum against Apollo, I could easily believe that he would not have met with the disgrace inflicted by the Muses bringing Phoebus himself to favour him and be *easily impelled to lay aside his lyre and take up the Phagotum.”

Happily, in addition to all this, the 19th century musicologist, Valdrighi, discovered a fingering chart for the Phagotum in the State Archives in Medina, dated 1565. Evidently written by Alfranio, it gives some idea of both the range and fingering system. It’s worth reproducing here, translated to English, as it gives some idea of the challenge in understanding the instrument.

The Tenor Chanter

| F | The little hole only closed at the back; and also you close that near hole which is not in the other. |

| E | All the hand off; that is open |

| D | The little hole and the middle hole in the front |

| C | The little hole and the key above and the last little hole as on the Flute. |

| B | The little hole and the key above and the near hole in front |

| A | The little hole and the key above; the first, second and third all together |

| G | All closed with the key below which sometimes is not there, that is to say, wanting. |

The Bass Chanter

| E’ | If there is here another key, it would be the 4th only as in the other Fagoto |

| D' | 3nd key only of brass |

| C | Middle key of brass only |

| B | 1st key of brass only |

| A | All off |

| G | Key, middle hole and the back hole with thumb |

| F | 1st key and 3nd hole with the back hole, the same as used on the Flute |

| E | 1st key and 2nd hole with back hole |

| D | 1st key and 2nd and 3rd holes with back hole. (to the left) The right hand 2nd hole and back hole is unison. |

| C | 1st key and 2nd, 3nd and 4th holes with the back hole |

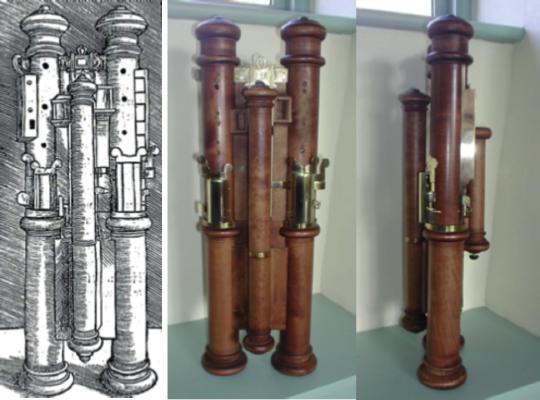

So, with much guidance and encouragement from Eric Moulder, I set about reproducing the Phagotum.

We worked out that if we took a piece of string the lengths of a tenor and bass crumhorn, and marked on them the position of the crumhorn’s finger holes, we could position the string on the woodcut, assuming a triple back parallel bore.

At the first attempt all the finger holes on the string just lined up perfectly on the woodcut. This also rather neatly showed that the end of each chanter was the little square boxes half way up and on the inner side of the chanters on the anterior view. And with the aforementioned upward facing reed on the bass side, there was enough bore to give the necessary pitch on the bass chanter.

The text clearly states that the reeds should be single beating reeds, such as you would find in the Boha bagpipes. And maybe they would work in the 10

note version of the Phagotum, with only 5 notes on each chanter. But try as I might, I couldn’t get a single beating reed to work on a 10 note chanter, encompassing an octave and two notes.

I tried long metal reeds up to 30mm long, short metal reeds down to 5

mm long. Some on a shallot, some free beating like in a harmonica. Fat ones, thin ones, narrow ones, wide ones. But none able to go an octave and two notes. So, in the end we decided to use a double reed as would be found in a crumhorn, which works well enough.

Here is a challenge for you all! Much has been learnt in the piping world in the 25 years since I built the reproduction of the Phagotum, and many makers now make excellent single reeded bagpipes. So if anyone out there has ideas of how you would make a parallel bored bass or tenor bagpipe work over this range, it would be great to hear from you. My next move (if I had the time) would be to arrange a straight pipe of 6.5mm internal diameter with finger holes, as per a crumhorn, and start trying reed options. Or, if you happen to have a tenor crumhorn lying around, then trying single beating reeds on that.

If you look at the keys on the chanters, it is clear that the fingering system is completely different on each chanter.

This does rather make it a mind game to play the two chanters simultaneously as it is like playing two completely different instruments. But it is possible to play simple counter melodies if you don’t try to think of anything else while you are playing.

The keywork did present some challenges to be able to cram the necessary mechanisms under the key covers and get the tone holes in the right place.

The switch, which is noted in the text, to turn on and off the drone, I have conjectured to be the tiny knob at the bottom of the drone tube which is just visible in the woodcut. And the switches for the two chanters I have conjectured to be the two strips of brass running down the insides of the windcaps at the back of the instrument. This may or may not be correct, but they do work, and I can’t think what else they may be.

Here is the most complicated windcap of a bagpipe stock of all time, showing the two chanter and single drone sockets.

Overleaf are pictured the two switches for turning on and off the two chanters.

There are one or two minor items in the woodcut for which I can’t think of a use but, in the main, I have managed to match what I can see to some function or other on the instrument.

Suffice to say, the instrument is really tricky to play and it is easy to see why it never made it into the modern age.

The Italian Job

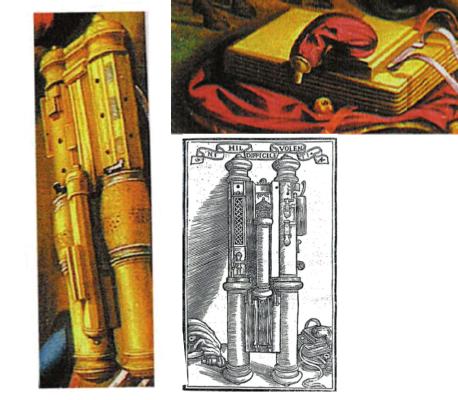

Eric and I were on a tour in Italy about 20 years ago with the group PIVA, and the musicologist and bassoonist Bill Waterhouse had set up a meeting with someone to talk to, in the hope that he could help us out any more about the Phagotum. He didn’t speak English and we didn’t speak Italian. But he passed me a picture of a painting, dating from around 1540, of a pastoral scene of Jacob and Rachel at the Well with a clear image of another Phagotum at the foot of the picture.

It was on display at an art exhibition in Mantua, so off we went to see it.

The scene was of the courtiers of Ferrara, playing at being shepherds, with

various instruments scattered around to indicate various meanings in the tableau.

We know they are the high courtiers as their faces are known from other paintings. The bagpipe clearly was there in the picture to indicate they were shepherds. But they couldn’t be seen with just any old bagpipe. It had to be the latest and greatest bagpipe available in the court at that time.

You can also see the crumhorn tucked onto the belt of the man wearing the leopard skin. No ordinary whistle or shepherd’s pipe for him either.

This painting is reasonably well known now for depicting the second Phagotum, but it wasn’t 20 years ago. The gentleman we met explained, as best we could understand, that the painting was usually reproduced with the bottom cut off as it fitted the aspect ratio of posters and postcards better, and who was interested in the thing on the ground anyway?!

Looking at the image of this Phagotum, you can see it is much simpler.

But the bag and bellows are identical to the ones in the woodcut from the book.

Clearly in boxwood and with silver keys without the swallow tail touches, it is a considerably simpler key system and with the same system on each chanter.

I am of the opinion that this instrument is of later design in the timeline of the Phagotum, as the woodcut was made around 1515 and the painting is dated at c1540. I suspect the complexity of the initial versions made simplifying it a necessity if it were to be made easier to play. In another lifetime it would be great to have a go at making this later model. But I suspect that’s for another enthusiast to have a go at.

A few additional things to note:

There is a record of Alfranio playing the Phagotum at a banquet held by Alphonso, Duke of Ferrara in Mantua in 1532. So it worked well enough for that!

The keywork on the woodcut version is interesting in that the front lower extension keys on both chanters have two “swallow tail” touches on them as you

would find on shawms and curtals of the 15th and 16th Centuries. This enabled shawm players to opt for left or right handed playing. But this is clearly a nonsense for the Phagotum, as it sits on your knee when being played and you couldn’t possibly use the other side of the key touches.

In addition to this, the two upper extension keys on the right hand chanter in the Posterior view look suspiciously like key flaps from another instrument, such as a shawm perhaps. There is a clear upstand on the lower of these two which would have a hole in it for the shank of the key to go in to actuate the key flap. It would seem his key makers palmed Alfranio off with bits of old keys they had lying around in the workshop when he came to get them to try and make the instrument work. The version in the painting seems to have keys made for the instrument without the “swallow tail” key touches. A much more elegant solution.

The bellows are somewhat unusual. On first glance, they look rather like the concertina bellows of a Musette de Cour, but if you look at the arrangement for the straps to hold the bellows to the body, and also to the arm, the hinge on the bellows would be towards the floor rather than towards the player’s hand.

This would have resulted in a most uncomfortable bellows action.

There is much debate as to the naming of the Phagotum. I am very much of the opinion that it stems from being like a bundle of sticks as in a fagot of sticks in modern terms. It is however sometimes referred to as the Phagutus, which I believe comes from deciding if the instrument is plural in having two chanters, or a singular instrument. But my knowledge of Latin word endings gets a bit hazy here.

Considerable confusion abounds on the internet, and in other publications which should know better, in that the Phagotum is often quoted as being an early form of bassoon. The confusion occurs in that a bassoon is also a bundle of four sticks and called a Fagott in German and Fagotto in Italian.

Bassoons have conical bores, however, and the text in the Ambrogio’s book clearly states it is a single beating reed (which may not be the case for the version with 20 notes). This stems from Lavignac’s Encyclopédie de la Musique published in 1927 which says that “Alfranio – il créa le premier bassoon”. This has become somewhat pervasive in the way of urban myths, and indeed if you put either

“Phagotum” or “Phatotus” into Google Translate from Latin to English it translates to “Bassoon”

There have been various publications over the centuries which examine the Phagotum, but for more in depth reading, I recommend the article written in the Galpin Society’s journal written in 1940 by Canon Francis Galpin, entitled

‘Romance of the Phagotum’. It is very thorough piece of research, including a full

translation to English of the relevant pages in Latin from Ambrogio’s Introductio in Chaldaicam Linguam. Without his work I would never have made progress in the reconstruction. If anyone needs sight of this article, please get in touch with me.

There has been occasional interest in the Phagotum over the centuries.

But not in the usual places like Agricola’s - Musica Instrumentalis 1528 and 1545, or Praetorius’s - Organographia 1619. There is a minor reference to the Phagotum in Mersene’s - Harmonicorum Libri 1636 and Harmonie Universelle 1636/7. The organological world is then silent on the matter until Fétis describes it in his Biographie Universelle des Musiciens 1860 and Werkelin in his Catalogue Bibloigraphique du Conservatiore National 1885. Luigi Valdrighi then publishes the fingering chart in Musurgiana Series 2 1895 and Nomocheliurgographia 1884. Along with Lavignac’s Encyclopédie de la Musique published in 1927, Groves Dictionary of Music gives it a mention in the 20th century. And many books and articles on the bassoon incorrectly reference it as the first bassoon. But Canon Galpin in 1940 is the very best of them all.

However, without Teseo Ambrogio’s Introductio in Chaldaicam Linguam in 1539 we would know nothing about this wonderful bagpipe. Possibly the most eccentric ever in what is a very crowded field for that title.

Tony’s email address, should you wish to find out more about this instrument or have any suggestions on reeds, is tony.millyard@talk21.com

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!