The Bagpipe Society

Seeing Double

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York houses a large and interesting collection of bagpipes, including a few unique musettes. One of them (the one in the picture below) caught my eye. It’s a late 17th century musette in the style of a French woodwind maker named Dupuis. There are only a handful of these dotted instruments left, and I figured it would be a fun experiment to bring this design back to life, for the first time since the Baroque period.

A trip to New York to admire it in person is still on top of my wishlist but luckily master builder Remy Dubois examined the musette before it was sold to the museum by antique dealer Jean Michel Renard in 2002. Discussing my plans with Remy was the logical starting point for this undertaking. According to his measurements, it’s a piccolo musette, or ‘musette du deux’, in A/D (pitch A=392), with a rather impractical drone configuration and a round petit chalumeau (the second chanter that extends the range upwards). It’s an early form of the petit chalumeau, where the middle part is a cylinder. Later musettes have a flat surface which makes it easier to fit the keys. None of my clients had asked for a piccolo musette, so I decided to make a more common ‘musette du trois’, in G/C, with a standard drone and petit chalumeau. Instead of ivory and ebony I opted for boxwood and African Blackwood, pitch A=392, with 12 silver keys. And then I thought about how cool it would be to have a set of contrasting musettes, so I made another one in Blackwood with bone dots, slightly higher pitched in A=415. And a few extra keys, 16 in total.

Unfortunately for me, my Great Ideas often involve a lot of hard work, trial and error and the occasional curse word.

Most of my instruments are based on historic musettes made by Nicolas Chédeville, his work is aesthetically and ergonomically unparalleled. As I didn’t want to compromise on sound and feel, the bore, bell, reed socket and key placement of both instruments are pure Chédeville. So is the layout of the drone bores. The turning and ornaments are more 17th century, especially on the foot joint of the grand chalumeau. This ensures the client gets the best of both worlds: a sound that blends in with an orchestra or chamber music ensemble, combined with the ornamental style of turning specific to the 17th century. The dots add a playful dimension, without being too dominating.

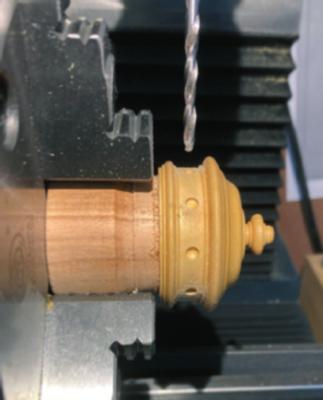

According to my completely unbiased opinion, that is. The dotted inlay adds a special touch to the instruments. Even in the Baroque period, this was not very common. In modern times, I’ve never seen it on a flute, oboe or recorder replica. Even my master Remy Dubois has never made one. I had no-one to consult when making these so I had to come up with a method myself. Luckily there’s a tool called a dividing head, which allows you to divide 360º into any angle you want. It can be mounted on the cross table of a milling machine, and then you can drill nice little holes with perfect accuracy.

I figured the best approach was to drill and ream the pieces, turn them roughly to shape, leaving 1-2mm of extra material to finish, and then use the dividing head to drill the holes. Next step would be to turn tiny rods of the proper diameter, a bit of superglue and you’re ready to finish on the lathe.

It’s not very complicated, but this took me two to three days for each instrument.

As I mentioned before, the African Blackwood instrument with bone dots has a few extra keys requested by the client. On the grand chalumeau, I made the high Ab key. It’s not a standard key as you can play an Ab on the petit chalumeau as well. The petit chalumeau has three extra keys, to extend the total range to two fully chromatic octaves, ranging from f’ to f’’’.

There is only one bar of music written for the highest key in the middle, c’’’#, in the third movement of Sonata VI from Il Pastor Fido, by our good friend Nicolas Chédeville. The client insisted on having this key, because it would allow him to play more of the flute and recorder repertoire on the musette. Adding these keys does indeed expand the musical possibilities of the musette, at the same time it presents the builder with a few challenges. As you can see in the picture, the springs for the highest keys also serve as springs for the key below. This is not a novelty, but how they used to do it in the 18th century.

Both instruments will leave my workshop soon, they will be played and, hopefully, loved by the players and their audience for years to come. Finding out how to recreate a design like this which, although very satisfying and fun, is nevertheless time consuming. My next instrument will be a standard musette.

No more crazy experiments, for now. Although I already have another Great Idea for a boxwood musette d’amore in E/A. Aaaaaaarghhhh…

Pictures by me, unless stated otherwise.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!