The Bagpipe Society

Bagpipes for the Norwegian Folk Tradition

Part 1: Introduction

This is the history of a personal project aimed at the development of a bagpipe to be used to play Norwegian traditional music, and to adapt and develop a repertoire of Norwegian tunes I could play on the pipes. In this article, I will discuss some musical, ideological and technical themes I encountered in this project, and how various aspects of those themes shaped the project.

My point of departure was simple: I had heard a variety of bagpipes in many different settings. I liked the sound and expressiveness of these instruments so much that I wanted to be able to play some version of pipes. In the Norwegian context there were, however very few sources that mentioned pipes being played, no traces of physical instruments, far less recordings of pipes being played like anything remotely possible to term as “Norwegian traditional music”. A few written sources mention pipes; the most cited is probably an advertisement in one of the newspapers in Oslo from 1849 where it is told that a certain Jens Christenson Klevgaard would perform “Sekkepibelyd fra Valdersdalen” (bagpipe sounds from the Valley of Valdres) (Berg, 1990:313-314).

I had no ambitions to play Irish, Spanish, French, Flemish or any such kind of music on the pipes. I wanted to be able to use the repertoire of Norwegian traditional music I already knew, and had played for years on the Hardanger fiddle. I started with three questions to explore:

- how do I get an instrument accepted as a «Norwegian folk music instrument» like the fiddle, willow flute, jaw’s harp etc?

- what are the necessary musical features of a set of pipes to work for Norwegian music, and what are the necessary/possible adaptions of the music to be played on the pipes?

- is it possible to make the pipes stable in intonation to conform to present standards of playing bands?

By now, I think that the interaction between these questions is more interesting than possible answers on each of them. In the beginning, I focused on the musical possibilities of the instrument, and how a bagpipe should be constructed to fit the fiddle music. Later, I spent more energy on how I could adapt playing techniques and music to fit the pipes.

A short history of my project

In 1991, I visited the Falun Folk Music Festival, and heard - once again -Swedish pipes, and - once again - thought that we should do something similar in Norway. The following autumn, I got in touch with Alban Faust, an experienced

pipe maker, based in Mellerud in Sweden, slightly more than 200km from where I live in Oslo. During the winter, we discussed by phone and mail, and Alban build a model with one drone and one melody pipe after a French type with double reed. I got it summer 1992, and started to practice and experiment. After further discussions with Alban, he added two more drones, and I also ordered a set of Swedish pipes. The reason for this was two-fold: I wanted to get a practical experience with the Swedish pipe repertoire; also; I had experienced that the first set of pipes I had, was too loud to use together with other non-amplified instruments.

Of course, I was not the only one who wanted to get pipes in some form to be part of the Norwegian folk music scene. In 1993, Kjell Stokke organised courses in bagpipe construction in Gjøvik, and by now, they have built more than 120 set of pipes there. Also, in Landskappleiken - the yearly festival and competition for folk musicians in Norway - Lasse Stand and Anders Hovde appeared in the section for “Old folk instruments” during the 1990s. Later, Elisabeth Vatn was probably the most active, with several different types of pipes.

Common to all of us, is a close contact with Alban Faust in Sweden. He has been instrumental (pun intended) in almost all bagpipe initiatives in Norway since 1990.

Part 2: Bagpipes in Norway why, and why not?

Motivation

In 1991, I wrote about my motivation for the project. I made two arguments; the first that Norway is one of very few countries in Europe with no trace of a bagpipe tradition; the second that it would be good for the existing folk music scene to include bagpipes in the tradition. Perhaps paradoxically, I argued that inclusion of a new element in the tradition would help to preserve it, as it might give musicians more expressive possibilities, and, increase the interest for the group of instruments termed “old folk music instruments”. But my personal interest was nevertheless to get a wind instrument that as far as possible would be suited to the peculiarities of the Norwegian Hardanger fiddle music.

Why no Norwegian pipe tradition?

Initially, I also speculated on why we had no existing bagpipe tradition.

The contemporary folk music scene builds on a continuous tradition several hundred years old, and the fiddle tradition contains several thousand tunes.

Instruments used in the tradition are not very different from those used elsewhere in Europe. The differences between the fiddle and the Hardanger fiddle may seem great when described in a context of Norwegian national pride, but, as instruments, they are basically the same, and the music has moved from

one to the other effortlessly, as it is also common for performers to master both varieties.

Also, jaw’s harp, flutes/recorders are used. So why not bagpipes, that are common elsewhere in European folk traditions?

It may be argued that a ’tradition’ for an instrument is a composite of several distinct traditions, like

- a social tradition where the instrument, the musicians and the music is valued.

- a tradition of music and musical context where the music belongs

- a tradition of instrument makers

- a tradition of performers

Musical raw material should be no problem. Even if we talk about ‘fiddle tunes’, ‘jaw’s harp tunes’ etc, tunes are to a large extent used on different instruments, but with the adaptions necessary to suit the instrument in question.

With not too much adaptions, I thought there would be lots of tunes that might be used on the pipes, as also my later experience showed.

Some instruments are technologically simple enough for anybody to make. With the half hour instruction I got as a kid, I am still able to make a working willow flute. But some instruments require high level skills to make. To make fiddles with a quality that is accepted by professional musicians, you need highly specialised instrument makers, and such makers need a market of a certain size to make a living. Instruments like fiddles and recorders are used in many countries and across several musical genres, and have a large international market. These two instruments are to a large degree standardised, maybe because these instruments have been used in the classical European art music. Bagpipes, however, are far less standardised, and are found in a large number of varieties in different countries.

But is it really very specialised crafts needed to build a bagpipe? Most of the work is by techniques well-known from other areas; sewing of leather, and the use of a lathe is used in many other connections. But there is one single skill that is important, and not used much elsewhere: the production of the reed. It is near at hand to think that experiences with reed from other reed instruments would be relevant, but the single reed of e.g. clarinets behave very different from the usual bagpipe single reeds. I soon discovered that more than 30 years’ experience with single reeds on clarinets and saxophones did not help me very much when I should handle bagpipe reeds.

Maybe Norway was too small a country to uphold two different and highly specialised instrument maker traditions, at least in the period up to the rise of National romanticism from around 1800. The period following is when folk music was invented - more precisely, the concept - not the music - and following that, a process of adapting to some extent the urban ideals of aesthetics, preferring beauty and consistent intonation to elements like rough sound, driving dance rhythms and personal intonation. To put it differently: Cows and barns are nice motifs for paintings, but one would rather not have the smell. In Hungary the shrill double-reed tarogato is replaced by the sweeter sound of an instruments that is like a soprano sax made of wood, but still called tarogato to keep its role as a national instrument.

The 1970s

In the 1970ties there is a change, with new interest for aesthetic ideals not valued in the national romantic context, e.g. contrasting the sound ideals of classical European violin playing technique. And this is precisely the time when the bagpipe is revived in Sweden. The historical evidence for bagpipe is not overwhelming in Sweden either. But there is some, and to a large extent in the district of Dalarna, that is the district that perhaps to the largest extent symbolise the ‘authentic’ Swedish traditional music. With some help from Dalarna Museum, the bagpipe soon got status as a real and authentic Swedish folk music instrument; in the words of Ronström:

“Among people affiliated to the field of folk music and folk dance the concept of the "Old Swedish Peasant Society" is loaded with strong positive values of long and unbroken historical traditions. Here the simple, old and authentic are important and the bagpipe is generally thought to be older, simpler and more authentic than almost any other folk instrument.” (Ronström, 1989:104) My point of departure was in fact the Swedish bagpipe revival. I probably was helped by the fact that the instrument already was established as a ‘real’ folk instrument in Sweden. In contrast to Sweden, the bagpipe projects in Norway took place in district with low folk and traditional credibility, like Oslo (my project) and Gjøvik, where they build a large number of pipes.

Part 3: The Music

My point of departure

When I presented the pipes at the Telemark folk festival in 1994, I wrote a motivation for the project:

What do you do as a wind instrument player by heart when you want to play Hardanger fiddle music? The first impulse is to forget your love of wind instruments, buy a Hardanger fiddle and learn the music on the very instrument that the music has lived on for some hundred years. Then, the urge to play wind instruments returns; first perhaps for the recorder, that, after all, had been used to a certain extent for the same music.

But after some experience as a fiddler, there are some of the qualities you really miss when you return to the recorder. First of all - you HAVE to breathe once in a while, and, therefore, interrupt the continuous stream of music. Then the recorder is not loud enough to match other instruments in ensembles, unless you restrict yourself to the upper octave. And of course, you lose the rich two-part sound of the fiddle.

This is common to several wind instruments. A saxophone is loud enough to be used in ensembles, but you still have to breathe, and multiphonics is too much of an effect, and too limited in variation to be an option for the two-string sound of the fiddle tunes.

So, even if the melodic part of the Hardanger fiddle tunes are possible to render on a (monophonic) wind instrument, I have never played - or heard - fiddle tunes played on wind instruments in a way that make them feel like real Hardanger fiddle tunes.

But I could never stop thinking about this. And with the pipes, I feel I have come a bit closer; it is loud enough, the sound is continuous, and it has a kind of polyphonic sound.

Practical work

In my early correspondence with Alban Faust, I tried to single out some musical features in the fiddle music that were important to me.

- sufficient range: the fiddle is normally only played in first position, giving a range of slightly more than two octaves

- a selection of available pitches to cover different fiddle tunings

- possibility to mimic at least part of the polyphony of the fiddle played on two strings, were the drone tone will change between strings, as shown in the figure.

Also, I regarded (and still do) the bowing patterns in the different tune types as essential ingredients of the hardingfele style.

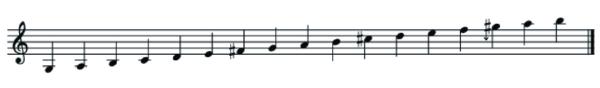

The pipes I knew at the time, could not articulate in the same way as direct blown wind instruments, so I decided to try to mimic the bowing patterns by way of embellishments of different kinds. (See overleaf for notation) I already had some practice with such techniques on the recorder and sax, so this was not something I discussed with Alban. Had I done so, I might have decided to try some pipe models with closed end and closed fingerings, that would have made such articulations possible.

But I wanted the flexible drone principle very much. Even if the pipes may give several tones at the same time, the drone is basically the same throughout. In two-string fiddle playing the drone changes when the melody moves from one string to another. I imagined a solution with two parallel melody pipes; one for each hand, and with three holes in front and one for the thumb on the back.

Left hand pipe gives the upper tones in the octave; while the right hand pipe plan the lower. But both pipes sound all the time, so that the pipe that at any given moment does not play the melody, will provide a drone. In this way the drone will change when the melody moves from one part of the octave to the other; much in the same was as when the melody moves from one string to another on the fiddle.

But Alban declined to try this, mainly from considerations of tuning: given the level of experience necessary to adjust the reeds to a given pitch and, at the same time, with the right interval between the pitches, he judged this to be far out of reach for a beginner on the pipes to master. I must admit that after several years of experience, I still struggle to adjust the reeds satisfactorily after contemporary standards of intonation. (I still have not found good synthetic reeds for my pipes).

Given the range I wanted, Alban asked if the Irish Uillean pipes would be a good solution - with a range of two octaves; used in ensembles, and with a certain flexibility in keys. But I did not want to use these pipes, mostly because their sound is so closely associated with Irish music, so I expected it to be almost impossible to have the instrument accepted as anything remotely ‘Norwegian’.

Then Alban suggested two possible alternatives for further work. One was with a French style chanter, double reed; the other a Swedish style chanter with single reed.

The double-reed chanter had d as fundamental key, and approximately one octave and a half by overblowing. Also, with double-holes and some fork fingering, a fair number of chromatic pitches as well.

The Swedish model also had d as base, a smaller range, and a smaller selection of available pitches.

For the b/b-flat and c/c-sharp pairs, one has to decide which of the pitches to use. The b and c possibilities are available when you plug one of the double-holes for the finger with wax or tape.

My wish for a large range led me to choose the double-reed chanter for my first set of pipes.

Then we had to decide on the drones. I’d like to be able to play tunes originally played on the two most common fiddle

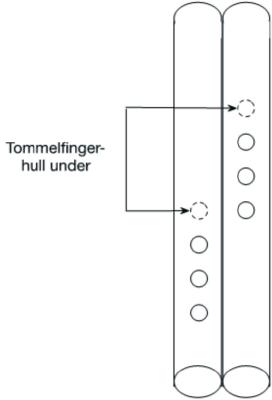

The upper part of the chanter on the Swedish model, tunings, g-d-a-e and a-d-a-e. The with the double holes for b/b flat and c / c sharp most common keys would then be d, a and g. As a beginning, we therefore chose a single drone in g, but with an extra hole on the side that could be unplugged to raise the pitch to a. In tunes in the key of d, the drone would be on the fifth of the scale; in the two other keys the drone would be the fundamental.

Testing and development

I did not get quite as large range as I had hoped at the outset. Therefore, many tunes had to be adapted; parts in the upper octave had to be transposed down, or simply not played. In some tunes, simple octave transposition is a way of variation; in my context, that meant I had to delete some parts, because transposing motifs down from the upper octave in such cases simply meant some more repetitions of one single motif. But in many fiddle tunes, the tonality changes in the upper octave; the second finger on the e-string might be a g-sharp; in many cases slightly low; while the corresponding pitch one octave down on the d-string will be a g natural.

Therefore, one option is to transpose the upper-octave version of the motif down one octave, but keep the alternative tonality with an augmented fourth instead of the pure (…well, almost pure).

However, in the key of D, none of my pipes had the augmented fourth available, so that option was not available in this key - the key that would correspond to most of the tunes as played on the fiddle.

As it turned out, however, I tended to transpose many of the tunes from D to G, first, because I wanted the root as drone rather than the fifth, as was the options on my first pipe. But then I discovered that in G, I actually had both versions of the fourth available. So then I could use the described variation technique.

These experiences also led me to ask for two more drones; both in D, with an octave between. In this way, I had the possibility to have the root as drone in the key of D, as well as both root and fifth as drones in the key of G. (See over.) To articulate the bowing patterns also worked well. As it turned out, I paid more attention to this in the gangar tunes than in the 3/4 springar tunes, where fingering, melodic structure and general feel for the groove were as important as a meticulous mirroring or the bowing patterns in the fiddle tune.

After a while, I also got Alban’s Swedish bagpipe model, and, even if it had a smaller range and fewer available pitches, I started to use it a lot. The reason was primarily because of the softer sound that worked better in ensembles, also, it was less physically demanding with lower air pressure required. The limitation in the either/or choice for b-flat/b natural, was also nice for one reason: by covering a small hole by wax or tape, I could play the b flat without fork fingering as required on the double-reed pipe.

But because of the limitations in available pitches, especially that I could not use both c and C sharp in the same tune, I could not play all the same tunes that I could on the double-reed pipes.

NOT FOUND: images/index-34_1.png IN [images/index-30_1.jpg images/index-31_1.jpg images/index-31_2.jpg images/index-32_1.jpg images/index-32_2.jpg images/index-32_3.jpg images/index-33_1.jpg images/index-34_1.jpg images/index-35_1.jpg images/index-35_2.jpg images/index-36_1.jpg]

Drone with a key

I could not give up the idea of emulating the hardingfele kind of polyphony with the changing drone strings. When I got a small d-drone in addition to the larger d- and g-drones, it struck me that it might be possible to furnish it with a key that could be operated by the left little finger. That gave me a drone that could change between d and e when played. Of course, a long way from the many sonorities of the two-string playing on the Hardanger fiddle, but it gave me an extra colour I used quite a lot.

Back to single reed

Nevertheless, I tended to mostly use the Swedish single-reed model, in a developed version called “Northern Uillean pipes"by Alban Faust. It has a single- reed Swedish style chanter, and three or four drones, that all can be activated/silenced by a small switch located in the part that holds the drones. In addition, all drones have a hole that, when unplugged, raises the pitch one whole note. With this flexibility in the drone set-up, it is possible to play in several more key than on the traditional model. But, as mentioned, the chanter still has less available pitches than the double-reed chanter. So why did I mainly stick to the single-reed instrument?

One key factor in playing pipes, is the adjustment of the reeds. Small errors in the adjustment may give large errors in intonation, and, in the absence of plastic or composite reeds, the skill of adjusting the reeds demands continuous practice. The procedures for single and double reeds have some similarities, but still need separate practice to be mastered at a level that makes playing fun.

There are also differences in the pressure required; on the single reed chanter, the lower notes demand greater pressure, while it is just the opposite in the double reed chanter. In short: it takes some extra effort to keep a sufficient level of skill, both in reed adjustment, and in playing technique, on both types. As long as the pipes are not my main instruments, I found it more than enough to keep one of the pipes do to say alive.

But the choice of the single reed chanter led to still another development: The process of transferring hardingfele tunes to the pipes made it clear that each melodic motif in the tunes typically has quite small range, typically within an interval of a fifth. The need for a large range therefore was much less when I started to rebuild the tunes and move motifs between octaves.

But it became more important to have access to both c and c sharp at will. That brought me back to Alban, and I asked him to make an extra key on the chanter. I got it in 2015, it is operated by the inner joint on the right index finger, like similar keys on clarinets and saxophones. The key gives c sharp when open, and with the small c sharp hole plugged, I have both c (closed key) and c sharp (open).

Conclusion

The project was quite successful for me personally, as I got a working instrument I could use to play music I like to play. That was also the main motivation for the project. The actual instrument ended up as Alban’s Northern Uillean pipes, with one small adaption in the form of the C sharp key. The main result was, in light of this, more on the musical side, in that I found ways to adapt tunes from the Hardanger fiddle repertoire to the pipes.

In the process of developing the instrument, and in transferring the music from fiddle to pipes, the lack of historic sources was actually an asset, as we were not restricted by many historic justifications that otherwise might have been important in a context of traditional music. The whole process was thus quite different from the development of the contemporary Swedish bagpipe tradition, where they had some historic sources and a few instruments to use as models.

My choice of cane instead of local material for reeds, as well as a bellows for air instead of a mouth-blown model - both important to get an instrument that worked well - was not made difficult by possible references to traditional sources in Norway.

The project was less successful in establishing a Norwegian bagpipe tradition. One reason is of course that it has mainly been a private project and I did not put much effort into marketing. I have used the pipes in a few concerts, and only after 20 years that I released an album with Norwegian music transferred to the pipes.

The larger instrument maker milieu at Gjøvik did not succeed in this either. Part of the reason is probably connected to the reed technology, in combination with the contemporary requirements on good intonation. A significant part of the time I have devoted to the pipes has been with reed adjustment; almost as much as actual playing. Recent developments in synthetic reeds may solve this problem, but until now, the sound quality of synthetic reeds has not been accepted by most players in Scandinavia. But I would not be surprised if aesthetic preferences soon adapted to the state of synthetic reeds.

A last point: In Sweden the bagpipe revival was to a large extent connected to local and national identity, located in the traditionally high-status district in folk music in Dalarna. With the attention given to local identity at the time of the Swedish revival, it is probable that the bagpipe added to the attention of Dalarna as an important historic district, and, at the same time, the bagpipe reveal was helped by the status of Dalarna. There are no parallels to this in Norway. Here, the bagpipe has more character of being a kind of ‘general folk music instrument’, with no specific local flavour. This may be an asset in a time when local identity is not as important in the traditional music genre as it used to be.

Tellef Kvifte is a musician, producer and professor emeritus. Details of his recordings, music and blog is at

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!