The Bagpipe Society

The Man with the Golden Thumb

Chaucer’s Miller and the problem of pilgrim pipers

Recently I viewed again the 1944 Powell and Pressburger film “A Canterbury Tale”, telling the interlinked stories of four “pilgrims” in wartime Kent. Its haunting cinematography, its mystical evocation of English landscape and history and its uplifting conclusion have long made it a favourite of mine, and there is a celebrated sequence at the start where a medieval falconer lets loose his bird of prey, which climbs and swoops - to be almost imperceptibly replaced by an RAF fighter plane, instantly transporting us from the 14th century to the mid-20th. Just before this time shift, there is a brief scene in which we see Chaucer’s pilgrims, or their ghosts, laughing and joshing with each other, and my latest viewing - maybe the fourth - was actually the first time that I noticed a particular fleeting detail, that one of the pilgrims is brandishing a bagpipe.

This, of course, is the Miller, probably the best-known bagpiper in English literature (the only bagpiper in English literature?). In his prologue to “The Canterbury Tales”, Chaucer tells us how this character “A baggepipe wel *koude he blowe and sowne/And therwithal he broghte us out of towne” *. In the movie “A Canterbury Tale”, the man representing the Miller holds a single-drone instrument, with the bag under his right arm and his left hand covering the lower end of the chanter. Perfectly feasible, but chances are that the extra who was allotted the role was a non-piper who had been handed an instrument, maybe a non-working dummy, and he simply held it as he thought best. Nevertheless, it is quite impressive that the producers, rather than simply obtaining a Highland bagpipe from the props store, researched and procured a plausible medieval instrument.

In so doing, they were adding to an iconographic tradition reaching back some 550 years. The first and best-known representation of Chaucer’s Miller is his depiction in the Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, dating from c.1400.¹ It is “captioned” “Robin with the bagpipe”. The instrument in question has a single, long drone and a short stub of a chanter. In our time, this was enough to enable Julian Goodacre to develop his interpretation, marketed as the “English Great Pipe” (I bought one in 1987 and it still works with its original cane chanter reed).

"Tales of the Canterbury Pilgrims", a book for young people

published playing what appears to be a recorder or a in 1904.

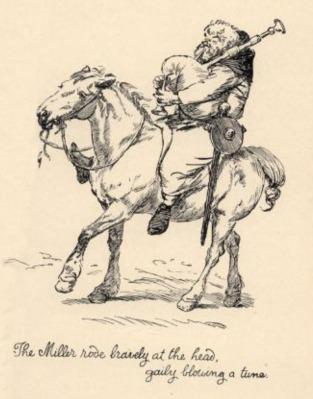

There are websites that have collated Chaucerian editions and illustrations, from the 15th century to the 20th,² and this makes it possible to track depictions of the Miller through the ages. On the whole, they have been consistent, with the Ellesmere original being widely copied or adapted, although there has been a tendency to make the dangerous and curmudgeonly Miller rather too benign and twinkly. One of my favourites is by Hugh Thomson from Darton’s “Tales of the Canterbury Pilgrims”, published in 1904. Some years ago, I extrapolated this image for the posters and programmes of a Christmas early music concert, on the grounds that it made the Miller look like a genial, bagpipe-playing Father Christmas - not exactly what Chaucer intended.

There are some variants, such as an 1833 illustration by Charles Cowden Clarke that shows the Miller (from behind) playing a two-drone instrument. An engraving of 1721 shows the Miller clutching a rather odd assortment of disconnected pipes. An 1841 “Penny Magazine” illustration by John Saunders has our anti-hero holding what appears to be a droneless bagpipe. These outliers are almost scrupulously authentic when compared to a woodcut in Caxton’s 1485 edition of the Tales. Here the Miller is illustrated as an upright, slim fellow who is tabor pipe. But while iconography has its limitations, a simple, single-drone bagpipe is the norm, as it seems to have been throughout medieval Europe. This has become a truism and it means that there aren’t any major organological lessons to be learned from depictions of the Miller.

More significant than the details of his instrument is the characterisation of this particular pilgrim and what this tells us about English attitudes towards bagpipes and their players, leading to the kneejerk prejudice that we are all familiar with today. Chaucerian scholars are apt to express this quite forcefully. The Miller’s bagpipe has been described as an “inauspicious instrument with which to lead a harmonious band of pilgrims.” ³ Another historian really lets rip, writing in 2017 that the bagpipe

“can still be found in some peasant communities. They need only a sheep’s stomach for the bag, and something long and hollow for the pipes and the chanter”. She continues: Assembled, they produce a sound of which there are many aficionados, among which I am not one. I take the view that distance - as much as possible - lends enchantment. So, perhaps, felt the unfortunate residents of villages on the way to Canterbury, *as the Miller brought the pilgrims out of town playing on his bagpipes…⁴

of Geoffrey Chaucer

We might bridle at such attitudes, but they are surely the response that Chaucer invited. In his general prologue to “The Canterbury Tales” he sums up the character of his pilgrims (fictionalised versions of real “types” in medieval society) by piling on descriptive detail and we are left in no doubt (here I give my own modern English precis of Chaucer) that the Miller was an obnoxious, drunken and corrupt brute - but not a man to mess with, because of his sheer brawn. He was a formidable wrestler and his strength meant he could lift a door off its hinges or smash it open with his head. He was red-bearded and resembled the bristles on a sow’s ear.⁵ His nostrils were black and wide, and his mouth was as wide as a furnace. He was a coarse loudmouth who was adept at cheating his customers, having a “thumb of gold” - this being a proverbial reference to the dishonesty of millers. “His thumb acquired a distinctive shape through feeling samples of corn,” writes one scholar. “*Through his skill and dishonesty, his thumb brought him wealth” *.⁶

on his nose from which sprouted hairs that

John Saunders' Cabinet Pictures of English Life,

1845

It is immediately after this litany of revolting characteristics - moral and physical - that Chaucer simply adds: “A baggepipe wel koude he blowe and sowne”.

This detail - specifying an instrument that medieval pictures often show in the mouths of devils - acts as a kind of Chaucerian punchline, summarising the character of the Miller.

Later, when the tale-telling has begun on the road to Canterbury, the Miller, so drunk that he can hardly sit on his horse, insists on jumping the queue and reciting his yarn, even though the Host protests: *“Abyd, Robin, my leeve [dear]**brother/ Som bettr man shal telle us first another”. * How come the Host had come to be on first-name terms with the Miller? In his 2001 anthology of bagpipeable early music, Pete Stewart explains that “the name of Robin had been linked with the playing of bagpipes for at least 120 years”, and he cites “Le Jeu de Robin et Marion” by Adam de la Halle, from around 1280, telling of a maid accosted by a knight whilst her lover Robin is away playing the pipes.⁸

Rather than mix it with the brutish Miller, the Host gives way and we hear a ribald tale about the cuckolding of a carpenter. It has episodes that would bring blushes to the cheeks of a “Carry On” scriptwriter, but also has one of the most telling musical details in all of the Canterbury Tales, when we learn that the libidinous student Nicholas sang and played the psaltery, with a repertoire that included “Angelus ad virginem”. If only Chaucer had told us what tune the Miller played on the pipes when he led the pilgrims out of town then we would have had a “genuine” piece of medieval English bagpipe music. As it is, “Angelus” serves very well.⁹

Underdowns, 1912

Medieval satirists and moralisers might have taken a dim view of bagpipes, but the instrument was plainly popular and highly regarded in some musical circles, including the royal courts (in his recent Chanter article, William Lyons traces the trajectory of the instrument’s status over the course of several centuries¹⁰). But beyond Chaucer and almost contemporaneous with “The Canterbury Tales” there is documentary evidence that the instrument was seen by some as an irreligious influence that symbolised all that was bad about pilgrims and pilgrimages.

In 1407, one William Thorpe was tried before Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, on a charge of heresy. It would seem that he belonged to the sect known as Lollards - often regarded as proto-protestants - and if found guilty of spreading false doctrines there was every likelihood that he would end his life at the stake. A 21-volume compilation titled “A Complete Collection of State Trials… from the Earliest Period to the Year 1783” (it can be viewed online¹¹) includes Thorpe’s own, lengthy account of his trial and defence, presumably written in prison, where it is thought that he died before the flames could claim him, although he states that would willingly embrace this death. Among the accusations made against him was that he preached that men should not go on pilgrimages.

Defending himself against this charge, Thorpe acknowledges that some pilgrims were religiously motivated but far too many of them were simply out for a good time in lively company, and the opportunity to splash their cash in dubious hostelries en route (I am simplifying his language and arguments somewhat). And - here is the clincher - such phony pilgrims will seek to have with them

…both men and women that can well sing wanton songs, and some other pilgrims will have with them bagpipes so that every towne they come through , what with the noise [of] singing, and with the sound of their piping and with the jangling of their Canterbury bells , and with the barking out of dogs after them, that they make more noise than if the king came there away with all his clarions and many other minstrels [spellings modernised].

playing a tabor pipe or a recorder.

Now here is a surprise. The Archbishop actually springs to the defence of pilgrim bagpipers. He tells Thorpe that:

“thou considerest not the great travail of pilgrims, therefore thou blamest that thing which is praisable. I say to thee that it is right well done that pilgrims have with them both singers, and also pipers, that when one of them that goeth barefoot striketh his toe upon a stone and hurteth him sore and maketh him to bleed; it is well done that he or his fellow begins then a songe, or else take out of his bosom a bagpipe for to drive away [with] such mirth the hurt of his fellow.”

Well, it is a somewhat eccentric argument (bagpipes as a pain suppressant?), but a refreshingly positive one from a period when bagpipes had what we would describe as an image problem. It is a problem that persists to this day, and which can in part be traced back to Chaucer and his brutish Miller.

References

-

Its name derives from the fact that it lay undisturbed for three centuries in the library of Sir Thomas Egerton, later Baron Ellesmere. It contains what is believed to be a portrait of Chaucer as well as miniature paintings of 22 of his fictionalised pilgrims. See <https://www.bl.uk/collection items/ellesmere-manuscript>

-

For example, https://chaucereditions.wordpress.com (Thanks to this site for all the illustrations used in this article.)

-

Michael Alexander, York Notes on Prologue to the Canterbury Tales (Harlow, Longman 1980), p.65.

-

Liza Picard, Chaucer’s People (Weidenfield and Nicholson, London, 2017), pp. 265-266.

-

“In the Canterbury Tales, animal imagery is often used to highlight certain aspects [of] a character according to medieval bestiaries, the sow represents dirty-minded, unclean people…Chaucer’s Miller shares his ability to play the bagpipes with various pigs that make their appearance in late medieval art.” See https://bit.ly/Chanter125

-

James Winny, Chaucer: The Miller’s Prologue and Tale (Cambridge University Press, 1971), p116

-

Ibid.

-

Pete Stewart, Robin with the Bagpipe (White House Tune Books, 2001). Obtainable via Julian Goodacre’s website.

-

See the version in, for example, Merryweather’s Tunes for English Bagpipes, compiled by James Merryweather (Dragonfly Music, 1989).

-

William Lyons, “Piping Down. The changing status of the bagpiper from the 12th to the 17th centuries”, Chanter, Spring 2021, pp 61-71.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!