The Bagpipe Society

The largest collection in one of the smallest villages

On a beautiful summer’s day in 2011, cabrette specialist André Ricros – also founder of the Agence de Musiques des Territoires d’Auvergne (AMTA) in 1985 – went to a musician’s banquet in the village of Cantouin. Set on the hills looking over to the wild flanks of the Cantal, dotted with picturesque villages gracing the foresty green slopes and overlooking a large blue lake created by a man-made dam, Cantouin is registered as one of the most ‘remarkable cities’ of France. With a bal folk organised in the salle des fêtes every week, beautiful gîtes in old stone houses and a high density of musicians, the village is a hub of culture, actively supported by the mayor. The particularity of Cantouin, however, is that it has been one of the centres for cabrette making and playing since the mid-nineteenth century. The cabrette is the symbol of Auvergne, a refined bagpipe that emerged in Paris amongst the Auvergnat diaspora in the mid-ninteenth century, lending its name to the bal musette and travelling, in time, back to its players’ homeland in France’s volcanic region. Joseph Ruols, “the best cabrette maker of all times” according to André, lives on the main square of Cantouin with his wife, Jeanette, and was an essential person for the museum as his infallible memory helped gather details on cabrettaïres as far back as the early 19th century.

Back to the banquet, André, both a well-known cabrettaïre and cabrette researcher, was asked to say a few words. Wine-glass in hand, he stood to make a short speech and, in passing, mentioned his dream of opening a cabrette museum, a project he had been pursuing, without luck, with a couple of other municipalities. A few minutes later, Monsieur le Maire, also known as André Raynal, took him to one side and told him he had something that might work and showed him a picturesque empty spot overlooking the Cantal volcano. In 2014 the Musée de la Cabrette was inaugurated and it has since been welcoming six to eight thousand visitors a year, revitalising the tiny village of 312 inhabitants.

In 2018, Monsieur le Maire decided to raise his ambitions for the village and took the initiative to extend the building and create an international bagpipe museum. The new blueprint included three more rooms in order to accommodate the most diverse collection of bagpipes in the world, larger than those at Brussels’ Musical Instrument Museum or New York Metropolitan Museum. Using his network, André helped the village by contacting friends and colleagues to acquire the instruments; the International Bagpipe Organisation helped him source bagpipes from Malta, Sweden and Greece.

Part of André Ricros’ impressive cabrette collection, purchased by the museum.

Visiting family a mere 200km away, I decided to go the extra mile and visit the museum with André on 13 August 2019. André picked me up at the station of Aurillac and, after a 3-hour train journey, drove an extra hour at break-neck speed through the twists and turns of the small Cantal roads. Only 10 minutes late, we were greeted in Vines, a cluster of houses belonging to the village of Cantouin, by Monsieur le Maire and the museum’s cabrettaïre guide, who followed us in as André showed me around the museum’s different collections. The first room offered an in-depth look into the world of the cabrette, beautifully presented with instruments, pictures, timelines, videos and explanations. I was particularly fascinated by the ‘jetons de bal’, the tokens that men used to buy by the score in order to be allowed to dance. Only men would purchase them and women would then be invited to dance, dancing for free all night. It was, André told me, a way to raise money at the dance. Behind the display, André opened a secret door and showed me over a hundred cabrettes and just as many spare chanters – musicians used to own several in order to play in all keys – hung on a wall in a riot of colour; this was his personal collection, amassed over 40 years, recently purchased by the museum.

We then stepped into the new extension and what a glorious sight it was!

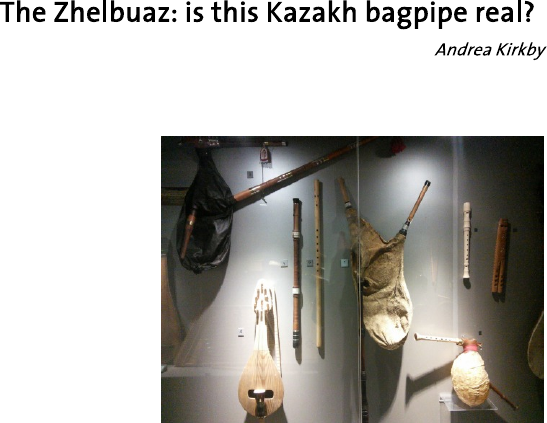

The glass cases hadn’t arrived yet, but André and Jean Louis had been working on the displays and I was greeted with a wonderful collection set out on the floor of the museum, instruments carefully labelled and organised according to regional areas: Northern Africa and the Middle East, France, Western Europe and Eastern Europe. I saw the pipes I had helped acquire and many more, a mix of historical instruments and custom-made ones for the museum, amounting to about 120 instruments, with an additional 300 cabrettes. Instruments ranged from the Iranian neyanban to the Turkish tulum, from the Polish sierszenki to the well-known Bulgarian djura gaida as well as an extensive collection of French bagpipes from the baroque musette to the lead-encrusted Central French Bechonnet pipes. The UK was also represented with some Northumbrian, Uillean and Great Highland bagpipes. They had complemented the collection with diverse iconography – statues, paintings, and small objects as trivial as biscuit tins and plastic figurines – in order to show the diversity of bagpipe representations all over the world. André went over each instrument and pointed out that although there were still a few gaps, there wasn’t much space left for new instruments (although any further instrument or iconography donations are more than welcome and would be fully credited, of course!).

André Ricros showing his cabrette collection,

purchased by the museum.

Part of the Western European display (imagine these in a glass case, vertical against the wall with explanation,

pictures and audio examples).

Bagpipes from the Maghreb and Middle Eastern collection.

We climbed up the stairs to a look at the final room: two short histories of the hurdy gurdy and the accordion through a wide collection of instruments. These will be accompanied by a temporary exhibition of a huge 3x2m painting of folk dancers and musicians by a local painter. I walked back down amazed by the vision of this small village, intent on making its mark both nationally and internationally through a museum of bagpipes and affiliate folk instruments. What an enterprise and how impressively it has been carried out by such a small team!

Dazzled by this small gem, we drove back to André’s hide-out, a tiny Hansel and Gretel-like house, taking a short-cut through winding lanes, regularly overtaking sleepy locals accompanied by respectably injurious French grumbling; I was having a great time, chuckling along. After a dinner of red wine, saucisson, comté and a delicious green been stir fry, Géraud, the area’s best chromatic accordion player turned up and I was treated to music from the time when musettes and accordions played together in Paris between the 1870s and the first world war. After initiating me to the cabrette (I managed to stumble through a tune, which I was quite pleased about considering it was my first time playing with bellows), André took a break and Géraud took over, regaling us with 1920s and 30s accordion musette music, setting our feet tapping as he deflty wove through waltzes, pasadobles, javas and foxtrots by the likes of Prud’homme and Vacher. A perfect ending to a perfect day.

Due to open in late-November 2019, this gem of a museum aspires to be the centre of the world for bagpipes. Not only does it host the largest collection in the world, it also features a 19th century bagpipe making workshop as well as a modern workshop run by Jean Louis Calveyroles, a cabrette maker responsible for running the museum and welcoming the visitors. So not only will a visit allow enthusiasts to gorge on a huge diversity of instruments accompanied by recordings, videos, iconography and a comprehensive explanation of bagpipes in their organological, historical and cultural contexts, it will also give an opportunity to try out small instrument-making tasks linked to the cabrette, with the potential of developing these into full-blown workshops, should there be an organised interest to attend one.

Yours truly trying out the cabrette.

Photo by André Ricros.

So next summer, when you decide to go to France for a good dose of local wine and cheese, I strongly recommend you to make your way to Vines, in the village of Cantouin, to drink in the mountain’s beauty, stay at a picturesque gîte, dance at the local bal and visit the world’s largest collection of bagpipes.

If you are curious about André’s work or Géraud’s playing, here are a few tips where you can read or hear them:

Ricros, André and Eric Montbel, 2017. La Cabrette, histoire et technique d’une cornemuse. Roim: AMTA

Ricros, André, 2012. Bouscatel, le roman d’un cabretaire. Riom: AMTA

CD: Bal en Haut-Auvergne, Géraud Felgines, Jean-Claude Rossignol, André Ricros.

By Balosso-Bardin, Cassandre International Bagpipe Organisation

From Chanter Winter 2019.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!