The Bagpipe Society

In Praise of Old Pipes

The Northumbrian small-pipes in their later classic form with seven or more chanter keys have an unusual significance in the traditional music of England, being one of the very few instruments which are entirely native, their creation being in the north-east of the country. These pipes have become so firmly rooted in the traditional music of Northumberland that their relatively recent origins, though never actually obscure, are easily forgotten. This is an instrument belonging entirely to the 19th and subsequent centuries, and represents an invention by a single individual, Robert Reid of North Shields, being the product of a working life of approximately 30 years beginning in the first decade of the 19th century and continuing until his death in 1837. His classic design consisting of a sophisticated keyed-chanter, together with 4 drones with their stoppered ends and tuning beads is the one reproduced today without radical alteration. The most significant subsequent variation is the introduction of chanters in modern concert pitch, most commonly in F, but also in G and less commonly, D. Reid’s pipes play comfortably at F sharp, representing the historical G one semitone flatter than present pitch which was in use in his time. However, the tonality of the usual modern chanter is still described as being in G though the actual pitch is likely to be concert F or even a little sharper; a situation that continues to confuse!

The Reids, Robert and his son James, were not the only makers employing that ingenious pattern. It seems to have been adopted, although in very small numbers, by some contemporary makers during the existence of the Reid workshop. In the later part of the century that pattern was also studied by the Clough family of Newsham. This extraordinary dynasty has their Northumbrian piping roots traceable at least as far back as the late 18th century and various members of that family were active in playing, teaching, composing, pipe-making and in one famous instance, recording. Tom Clough’s performance, preserved on a 10 inch 78 record and issued by by HMV in 1929 is still a subject of close study as an admirable example of early style and technique. In pipe-making, the Cloughs, chiefly Tom Clough (III) adopted what was still essentially a Reid invention but adapted to make it very much their own. Theirs was a very utilitarian design serving the needs of their compositions and playing style, though displaying little of the craftsmanship of the Reids. Nor was this seen as a commercial opportunity. They made chiefly for themselves and perhaps a few privileged pupils. Few in number, Clough pipes are prized today for their playing qualities after restoration and also for their design innovations concerning keywork.

Reid 7 key chanter. A classic seven keyed Northumbrian chanter viewed from all sides. All keys are operated with the right hand thumb with the exception of two seen on the right of the first image, worked with the left hand little finger.

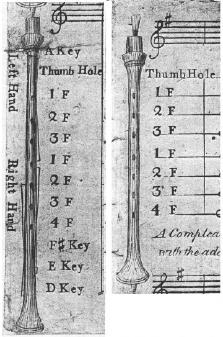

An earlier and simpler form of Northumbrian small-pipes precedes this Reid keyed design. It, too, has a stopped chanter; that is to say the end of the chanter is blocked so that no sound can be produced until a singer finger is lifted, all others remaining on the chanter. This strict “closed-fingering” style with the observation of minutely brief gaps between sounding notes persists as the basis of the best traditional practice. This simple stopped keyless chanter together with three drones, and usually made in ivory and silver, was also known well beyond the Tyneside region. It is to be seen in a painting of Joseph Turnbull held in Alnwick Castle, seat of the Dukes of Northumberland. Turnbull was piper to the Countess of Northumberland and this portrait, thought to date from around 1756, provides a clear statement of the social status of this less complicated but evidently costly instrument. A more familiar and precise illustration of such a chanter is shown in the engraving of the fingering chart included in the tunebook published by William Wright with the presumed collaboration of John Peacock. This is the collection now popularly known as Peacock’s Tunebook, the earliest printed collection of tunes for that instrument, dating from around 1800. Included in the back of that book is a detailed engraving demonstrating that the simple chanter was still current approximately fifty years after Turnbull’s portrait. Also shown is the first evidence of a development of this simpler form: “J. Peacock’s New Invented Pipe Chanter with the addition of Four Keys”, indicating that this was an important transitional time in the evolution of these pipes.

Chanters, keyless and with four keys, from the engraving in ‘Peacock’s Tunebook'

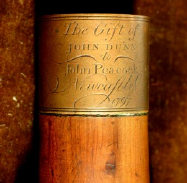

The name most commonly identified with this simpler form is that of John Dunn. Dunn was closely associated with the Newcastle engraving firm of the famous Thomas Bewick, occasionally producing rollers and other components for their printing equipment. However, as well as being a cabinet maker and turner of mechanical parts, he was capable of turnery of the utmost delicacy, and several sets of his survive, almost all of them in ivory and silver. One particularly fine example of his work is the elaborate set of pipes made for Robert Bewick, son of Thomas and himself an accomplished engraver, now in the Chantry Bagpipe Museum in Morpeth. Other pipes by Dunn are to be seen there, though the one perhaps best known is also the least typical. It is described on its drone ferrule as ‘The Gift of John Dunn to John Peacock, Newcastle, 1797. Peacock was reckoned to be the finest Northumbrian small-pipes player of his time. Unusually for Dunn, this gifted set has brass ferrules rather than silver, bone mounts, instead of ivory and drones made from a grainy rosewood less capable of displaying fine turnery detail than the costlier ivory or ebony. Dunn is most probably the intended maker of the 4 key set illustrated in Wright’s tunebook although the few of his surviving examples do not closely resemble that chanter shape. Were there other makers of these costly items? Perhaps so, but there seem to be no surviving simple sets that are demonstrably not by Dunn.

It might erroneously be assumed that there were several makers producing sets of pipes in generous numbers to meet the demands of an eager public. This is not so. Northumbrian small pipes, whether keyed or un-keyed were complex delicate items constructed from expensive materials and intended principally for the use of the relatively well-off. Compared with, for example, the probable number of violins, these pipes were relatively rare instruments at the time, constructed within a very restricted geographical area by very few individuals and intended only for a smallish clientele that was able to pay for these costly items as well as their maintenance. Such expertise was in the hands of very few individuals and the provenance and understanding of these pipes was consequently very vulnerable, as was later to become evident.

After Robert Reid died in 1837, his son James, a capable but less gifted craftsman, continued the business although he was eventually obliged to diversify, producing non-musical turned items as well as pipes. He lived until 1874 but by then, the fashion for Northumbrian small-pipes around Tyneside was already in decline. Whilst interest in small-pipes was diminishing, other instruments were thriving. The violin trade was increasing and many instruments were being imported from Germany at very affordable prices. Flutes too had become more sophisticated in their design and were being manufactured in increasing numbers. Perhaps most significantly, a new and exciting instrument had also been invented; the concertina. This had been patented by Charles Wheatstone as early as 1844 and the ledgers of his firm, now held in the Horniman Museum, London, reveal that the production of concertinas in large quantities had begun shortly afterwards. Concertinas are an attractive first or second instrument for present-day pipers and in the mid-19th Century, the appeal of that new invention must have been especially powerful: a free-reed instrument providing extended use without needing constant adjustment, and working straight out of the box. Once these were being produced in industrial quantities and relatively inexpensively, the disadvantage to pipes and pipe-makers would have been inescapable.

Drone stock from Dunn pipes presented to Peacock

Not only had it become more difficult to procure Northumbrian small-pipes; the expertise in maintenance and also in reed-making seems also to have become scarce. An interesting instance of this difficulty is mentioned in a letter from the artist Charles Keene to his friend and fellow piping enthusiast Joseph Crawhall in 1873. He writes: “I am waiting for a reed I ordered half a year ago of old (James) Reid of North Shields”. Presumably Keene continued to wait, remarking two years later to the same correspondent: “I was sorry to hear of poor old Reid’s death. Who is to make chanter reeds now?” No doubt a good chanter reed could have been procured at this time, the difficulty being exactly how and where to do so. Even at present, this is not an entirely straightforward matter.

In our own times, players new to the pipes quickly discover the extraordinary maintenance requirements of this instrument with its vulnerability to temperature and humidity-changes necessitating very minute adjustments to the reeds. One needs either considerable personal expertise or access to professional help. Fortunately for most present-day pipers, this is a problem with an accessible solution, and in today’s very connected society, it is hard to imagine the difficulties this must have presented to anyone in earlier times needing advice or a replacement for a damaged reed. The consequences of this dilemma are often very visible among those examples of old pipes that have survived. Substantial alterations to the hole sizes and effective positions are common, these often indicating an attempt to bring a chanter into tune with a reed that may have been far less than ideal. Also common is the evidence of alteration to the bore, the conversion of ivory mounts into tuning beads, as well as the cannibalisation of earlier three-drone stands to provide a set of four, often with inappropriate additions and alterations to existing parts. All these efforts are perfectly understandable; these instruments were in the most part not regarded as valuable antiques, but as the only ones available, which had probably been neglected for a considerable time and which might be put to some interesting musical use by anyone who had a mind to do so. How different from our present time when high-quality instruments are available to order, when requests for advice can be answered from afar within minutes and when an original Reid set can fetch several thousand pounds!

Fine examples of early Northumbrian small-pipes are not difficult to find and many beautiful examples are to be seen in the musical instrument collections of major museums. A particularly fine private collection, formerly owned by William Cocks and now in the possession of The Society of Antiquaries, Newcastle is presently accommodated in Morpeth Chantry Bagpipe Museum. This collection consists of a good number of early Northumbrian pipes, assembled during a period when the importance of these pipes was not widely appreciated and when they could be bought for relatively modest prices. As for early pipes in working order, there are many examples now in private ownership and in regular use, which have been sensitively restored. These pipes have a natural interest as antiquarian items representing the origins and development of the present-day pipes owned by most players. However, much can be learned from these old pipes, which is also of value from a musical point of view, rather than being of historical interest alone

From an instrument maker’s perspective, the Reid chanters appear extraordinary objects, a fine example of ideal design, which mysteriously seems to have emerged fully formed without any apparent evolution with the exception of the rare examples of 6 key chanters lacking the D sharp key. Some changes of detail occur throughout Reid’s career but what remains evident and constant is the extreme economy and functionality of the design, in which little is purely decorative. Every detail is generally present for a practical reason, to a degree that is remarkable. The very compact keywork also conforms to that principle. The outline of the keys remains close to the chanter stem with no part unduly projecting, a particularly neat construction that reduces the vulnerability of the keywork to accidental damage. Players will notice an immediately comfortable hold on the chanter, with keywork that is lightly and evenly sprung and with pleasantly rounded key-touches which accommodate differing angles of finger action. Such characteristics are evident on some finely made modern pipes but they are by no means universal. These physical aspects have more importance than the purely aesthetic quality and they do have an impact on the playing experience. The lightness of touch, the relatively large finger-holes (which may often be part of the original intention rather than the result of subsequent over-tuning), as well as the characteristic F sharp pitch, are very favourable to the playing of rapid staccato passages typical in some of the older repertoire. This effect is even more noticeable when playing on a Dunn-style simple chanter capable of playing only 8 notes, an ideal chanter in fact for much of the ‘Peacock’ repertoire. Other factors help this very rapid response, one of them being the simpler profile of the bore. A narrow cylindrical bore is never acoustically a true cylinder because of the interruptions of the relatively large finger holes, and with a keyed chanter, that effect is more pronounced. Rapidity of response is also encouraged by the very narrow external diameter of the Dunn chanter, 9 mm being typical. That is around 2 mm less than the Reid diameter but sufficient to make an audible difference. The response of these old chanters cannot make you into a better piper, but the experience of using them can make the playing of some difficult passages seem rather easier and they do provide good insight into some of the performance aspects of the early small-pipes repertoire, whatever set of pipes is actually being used.

Naturally, this valuable experience can only really count when the pipes have been sensitively restored with regard to the intentions of their original makers. Fortunately, we are long out of those Dark Ages when anything could be done to a fine old set of pipes just to provide a playing instrument in the absence of any others available. Very much more is now understood about the appropriate treatment of historically significant instruments, both in their restoration and conservation. That understanding has come about through the wider awareness of early music, which has emerged over the past few decades. Internet resources, as with any other area of specialist expertise, now ensure that anyone can easily gain some understanding what is regarded as good practice in this field. Principles of working with very old pipes should really form the scope of another article but perhaps it is worth briefly exploring some ideas here, which are applicable in the treatment of any significant old musical instrument.

Instruments that have survived until the present have passed through many hands and in most cases will have undergone some modification, often displaying very differing levels of skill and understanding. Work was undertaken without regard for the historical and conservation precautions which are now commonly respected. These days, any adaptation can become very controversial when a museum instrument is to be put in playing order for demonstration purposes. This issue presents a number of additional dilemmas when the instrument is in private ownership. Should it be made to play and be used frequently, and if so, what modifications are permissible? A private owner might understandably say “Well, it’s mine and I’ll do what I like with it”, an opinion that is sometimes modified with the realisation that the financial value of an old instrument may be substantially diminished by any such change if it is irreversible.

Sentimental myths often arise in such discussions about the fate of old musical instruments. One such is that an instrument absolutely must be used and heard and that it is somehow disrespectful to it or to its maker to preserve it in a silent state. On the contrary, it is often the case that an instrument is of greater importance in its original state, in terms of the historical information it contains. This evidence may be compromised by restoration to playing condition if much modification is carried out. A similar myth holds that instruments inevitably deteriorate if they are not used. Not so; when properly conserved, musical instruments generally remain in a stable state. What really wears them out is using them - a process that applies to all other known artefacts as well. These issues are relevant to the treatment of all antique musical instruments. However, considerations that specifically concern old pipes usually indicate that they can often be made to work without harm, provided that they are not impossibly fragile, that no irreversible modification is permitted, and specifically that no material is removed from the original work, including the adaptation of the socket shape and the sharpening of any tone holes. Even so, it remains doubtful whether historically valuable pipes should be played on a daily or otherwise very frequent basis.

Much has been said here in praise of and in defence of old Northumbrian small-pipes. The delicacy and inventiveness of their design is successful, delightful and very instructive. However, one characteristic they lack is robustness and durability. This is not a failing on the part of their makers; pipes from the workshops of the Reids or Dunn were never intended for intensive use and their customers probably regarded them, for the most part, as parlour instruments for occasional playing. There will have been many subsequent exceptions to this pattern of use, and the effects remain highly visible on some surviving examples. For instance, it is impossible to know the state of Billy Pigg’s Reid chanter when he first obtained it. What is certain, though, is its present state and the degree of extreme wear evident after decades of very energetic use. His was an ebony chanter; ivory pipes are even more vulnerable in this respect. The delicacy of early pipes renders them clearly unsuitable for intensive use and this is especially true for a particular category of player. A new phenomenon in piping has only recently become possible; that of the fully professional Northumbrian small-pipes player. Much of this has been made possible through the efforts of the late Colin Ross, whose redesign of the Reid concept, retaining all its basic characteristics but bringing to it enhanced robustness and the ability to sustain far more frequent and prolonged use has been highly influential among the best modern pipe-makers. His innovations include improved reliability, an interchangeability of chanters, sometimes in different pitches, and keywork that in certain aspects reflects some of the characteristics of keywork on other later woodwind instruments, including lined key-slots and a more common use of lengthy keywork to extend the range. Also important in this is Ross’s work in establishing the design and dimensions of an effective standard chanter reed, the making of which he taught through classes, a published instruction booklet and demonstration videos which may be found on YouTube. This has helped to bring about a standardisation of pitch, especially important when playing with other fixed-pitch instruments such as concertinas or keyboards. We do not know what importance early pipe-makers gave to precise pitch, but since these pipes were probably intended as solo instruments, or to be played in the company of fiddlers, exact fixed pitch may not have been of paramount importance. Incidentally, a commonly established pitch standard is almost certainly a recent development to accommodate the modern practice of group piping. Nevertheless, there are two pitches in current use for standard chanters. One is concert F, a universal musical standard which allows those pipes to be played with other fixed-pitch instruments without tuning difficulties. A sharper pitch, 20 cents above concert F is also common. That higher pitch has no historical precedent and is unique to Northumbrian small-pipes. It may also have its advantages though they are not easily apparent. Other less controversial developments are also in progress extending the capability of Northumbrian pipes. In performance, too, those pipes are appearing in wider musical contexts and sometimes in the company of classical musicians. This remains a living and evolving field and, no doubt, the future will hold further developments which may be celebrated. I hope, though, that I’ve been able to suggest that a sympathetic attention to the pipes of the past can lead to a greater understanding of our present-day instruments and their music. This article is a revised version of one first published in the Journal of the Northumbrian Pipers’ Society 2010 and appears here with permission.

Pipes by Dunn, formerly the possession of Robert Bewick

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!