The Bagpipe Society

Bagpipes in the West Highland Museum

Bagpipes in the West Highland Museum by Ross Calderwood and James Merryweather

In April 2019, the two of us visited Fort William to examine properly the bagpipes we had previously seen on display at the museum there, inaccessible behind glass but recognised as, at the very least, interesting.

Having gained the interest and trust of the curator, we were also shown boxes of complete and incomplete bagpipes which the museum had insufficient space for display. A few of those assorted bits were awful, some were quite interesting but of indeterminable provenance, and some were impressive and fascinating. The three display bagpipes were little short of exciting and we were allowed to handle and examine them from every aspect.

As might be expected, the labelling was sometimes prosaic, sometimes a little fanciful and occasionally highly doubtful or just plain wrong. Nevertheless, the six exhibits and collections we examined consisted of some remarkable specimens for which we present here our preliminary interpretations, hoping that other bagpipe enthusiasts will add to our knowledge of this small but undeniably valuable collection.

The most intriguing has to be the so-called Faery Pipes of Moidart. They have been described and discussed by Keith Sanger (1), but we were determined to make up our own minds about them. The parts are mixed, but some might make a significant contribution in bagpipe history as discussed below. If those few parts are as old as they seem to be, they are rare.

While we have the opportunity, we might mention the collection owned by Inverness Art Gallery and Museum, which includes some rarely seen bagpipes, including several eighteenth century Union Pipes (one with reeds and its own home-made carrying case (2)), several semi- and almost complete Scottish Smallpipes, a set of three drones not entirely unlike those shown in the well- known illustration of Geordie Syme, Toun Piper of Dalkeith, 1789(3) and, of course, lots of Great Highland Bagpipes (GHBs), some of them quite important instruments.

Unfortunately, a few years ago the museum was updated by a professional display company who had little idea which bagpipes should be exhibited and how. The public display is satisfactory – no worse than the dusty old cases it replaced – but a lot of good material languishes in storage, rarely seen by anybody. Thus, few people know about the Union Pipes, which we consider to be of significance, both organologically and in the pretty well undocumented social history they represent. We know the last owner of one set – even a photograph with him exists with them in his arms (4) – so the intrepid researcher would have a great starting point for finding out their history and usage at or around Tain, not far from their current location.

THE FAERY PIPES OF MOIDART – (allegedly) played at Bannockburn 1314. Display Case Label: “A set of bagpipes with chanter, blow-pipe and single drone. Believed to be one of the oldest sets of pipes in existence the chanter, blow-pipe and top half of the drone are original and bag sockets are modern replacements. The pipes, by tradition, were long in the family of MacIntyre, hereditary pipers to Menzies of Menzies. The pipes passed to Robert MacIntyre who was piper to MacDonald of Kinlochmoidart. He emigrated in 1790 and before going gave the pipes to Lt Col Donald MacDonald of the Royal Scots, 7th of Kinlochmoidart, so that they should not leave the Highlands. The story associated with the pipes varies depending on whether the teller is a MacDona1d or a Menzies. According to the lender, before the battle of Bannockburn, MacDonald of ClanRanald’s piper MacIntyre was busy fashioning a new chanter when a fairy told him to make an extra hole for the sweeter music ‘the like of which had never been heard before’ and which ‘would strike fear into the hearts of the enemy’. The pipes were played at Bannockburn and subsequently never at a losing battle. The same story is told about Menzies of Menzies. The Pipes are still playable. When restored in the 19thC and played the tone was described as somewhat loud and harsh. From their having only one drone, the air or melody is heard more distinctly than a modern bagpipe. On Loan Lt Cdr David Robertson MacDonald, 14th representative of the Kinlochmoidart family.”

Ross: According to Keith Sanger (5), these bagpipes date back to 1674, which would make them the oldest fragments of bagpipes in the UK. The rough outline of the story is that Donald Roy Macintyre was given by Campell of Breadalbane twenty-four pounds to go to Edinburgh for the purchase of some pipes plus forty pounds to learn his trade as a piper and four pounds for clothes. The pipes were passed down through the MacIntyre family until they came to Robert MacIntyre.

MacIntyre emigrated between 1810 and 1812 and the pipes were kept in Scotland by the local laird MacDonald of Kinlochmoidart and they were seen at the time as having great antiquity.

The pipes consist of three original parts, a tenor drone top, a chanter and maybe the blowpipe. These three parts do not have the same quality of turning as each other, so probably do not belong together. The wood is hard to identify due to its age. The drone top is conical and not dissimilar to older European images as well as being similar to the “Geordie Syme” pipes in Inverness Museum (6). It has a horn ferrule and there is no end cap. If there once was an end cap, it has been lost or its ‘absence’ might be a design feature. There is a metal ferrule halfway up which looks like a later add-on, maybe to assist a repair. The turning is quite crude. The chanter is of a lighter wood, which reminds me of yew or fruit, and it is of better quality than the drone that nonetheless has a really well-turned basal joint. The chanter’s low leading note (low G) has been drastically flattened with new holes, and of what look like the original holes, one of them is plugged with a piece of dowel. I assume that the opposite hole block has fallen out. The octave (high A), has also been modified, sharpened and the old hole filled with a dowel. The blowpipe is roughly square in section and doesn’t look anything like the other two parts. It is probably unrelated.

James: Played at Bannockburn? At the battle of 1314? Did they know that? Does any part of this instrument look 14th century? Also, I find it hard to agree that the drone bell resembles those depicted in the Geordie Syme portrait or the Inverness Museum drone set, other than its being conical rather than distinctly tulip-shaped or trumpet-flared. I suggest that its conical simplicity is a reflection of the maker’s skill level, not deliberate design. Even I, a novice wood turner, could create a more elegant shape. [Note: in the display case, on the right, a spurious comparison with a completely different sort of Scottish bagpipe … and is anyone wondering what the little chick is doing in a bagpipe display case?]

**MUSETTE DE COUR. ** Display Case Label: “FRENCH CAULD WIND PIPES Bequeathed by Prince Charles to the Stewart wife of his Valet de Chambre and purchased by I Skene of Rubislaw, Rome 1802. The museum purchased these important pipes in June 1972 from the Skene-Tytler Trust. WHM Coll.”

Ross: This complete set – bag, bellows, grand and petit chalumeaux (chanters), and shuttle drones – is extremely well made, fully of ivory. From the maker’s viewpoint, there is a really nice taper for the bellows-to-bag connection.

James: Compare this set with the Wikipedia illustration of a musette de cour in the Berlin Musical Instrument Collection (7) They are so alike that one wonders if they came from the same maker’s workshop.

CULLODEN PIPES Display Case Label: “BAGPIPES Said to have been given to Prince Charles and picked up on Culloden Field. However, much of the set is modern. The drones are of ivory and boxwood. WHM 743”

Ross: The overall shape reminds me of mid-19th century GHBs. My impression is that they are very difficult to date and could be 18th century but more likely Victorian. They are made of box wood with highly decorative ebony inlay, reminding me of the false fontanelles discussed by Jane Moulder (8) They are finished with marine Ivory, bone and cow horn. The rings on the drone tops have got schreger lines (9) which indicates they are made from elephant ivory.

BAGPIPESArchive Box Label: “An incomplete set of GHBs said to have been found in the arms of Alaster McLeod killed at Culloden. Mrs Muriel Lee Bequest WHM 2334”

Ross: A remarkably good set of 18th Century pipes,

(1st class and too good to be hidden in storage). Similar to a set in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow. They are about the same size as bellows blown Lowland bagpipes, the drone bells resembling those depicted by Egbert van Heemskirck (1634-1704) and other 17-18th bagpipes (10). It is difficult to identify the timber. My guess would be that it is from the maple family, but it could be cherry.

**LUCKNOW PIPES 1857 **Archive Box Label: “CHANTER Believed to have been played by Sergeant Campbell at the relief of Lucknow

[1857]. Miss D. Hannaford. WFM 2409”

Ross: A first class set of mid-18th century GHBs. They are made from ebony with marine ivory and have a Henderson chanter. Peter Henderson started making pipes in 1880 so the chanter is not original to the pipes. There are old ribbons that, with other hints, suggest that bag cover could be contemporary. A modern piper would be happy to play this set.

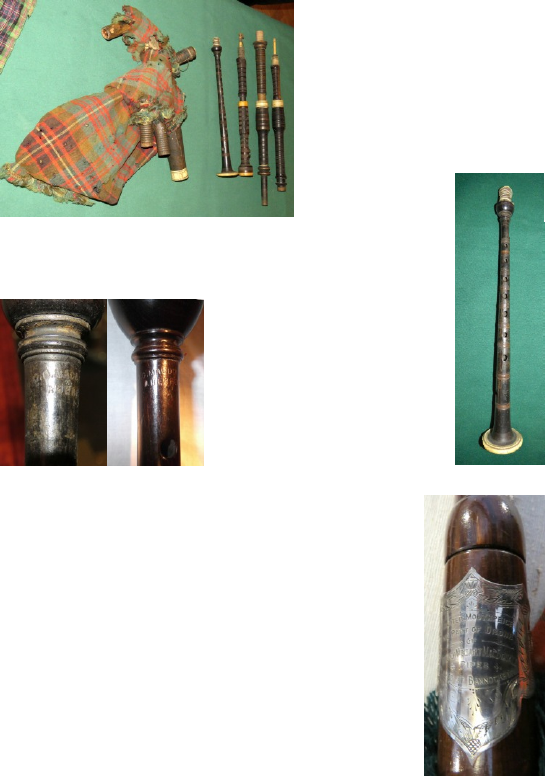

**BAGPIPES (Bag of bits)**Archive Box label: absent or we failed to record it.

Ross & James: Parts of at least three instruments presented as one, of varying quality plus some false replacement parts.

- A well-made three quarter or ‘reel pipe’ chanter, probably by Gavin C.

MacDougall (1887-1910) of Aberfeldy, short-lived son of well-known bagpipe maker Duncan MacDougall (1851-1898). The chanter has a maker’s stamp, though the initials of: “… MacDougall Aberfeldy”. are difficult to decipher. That they are likely to be G. C. for Gavin C. MacDougall is confirmed by the matching maker’s stamp depicted on the Bagpipe Museum’s website page about that maker (11) The chanter has been extensively repaired and has an ivory sole.

- In the main illustration.

Two tenor drones bottom sections and one tenor top, which look like Glen (J&R?) in style but could MacDougal. They are about the same period as the chanter in 1. Above.

- In the main illustration.

A broken, ebonised bass drone, a tartan bag and cover plus a set of roughly made stocks that might all or partially once have been joined up with number 1. and 2. above to form a ‘set’ of pipes for display.

AFTERWORD

The small collection housed in Fort William is little known, yet it includes some important bagpipes and bagpipe fragments. The Faery Pipes (1), although somewhat over interpreted in the labelling, contain some parts that might be unique in British bagpipe history, though telling which is original and which is replacement is difficult. The drone seems to have two phases of manufacture, one skilled, the other less so. Was the lower, better made section made to receive the silver plaque that tells the bagpipe’s somewhat doubtful history? Any bagpipe could have been played at Bannockburn the place at any time, but during the 1314 battle seems extremely unlikely. Another unanswered question is: who named them The Faery Pipes and why?

The Musette de Cour (2) is as intriguing as it is beautiful, well worthy of further investigation. BPS musette people wishing to know more, please ask us for our assistance. At a mere 70 miles away, we probably live nearer than you.

The rest of the collection – essentially four Scottish instruments, two of them 17-18th century – particularly interested Ross, who has commented on them with the enthusiasm they deserve. Now that more people are aware of their existence, perhaps they include researchers who would wish continue and refine this preliminary survey. Contact Ross (info@lochalshpipes.co.uk) or James (huntsup@theyorkwaits.org.uk).

(1) Sanger, K. (2013). Fact and Fiction; The ‘Bannochburn’ or MacIntyre Pipes and their owners. https://www.academia.edu/7961285/Fact_and_Fiction_The_Bannochburn_or_MacIntyre_Pipes_and_t heir_owners

(2) Merryweather, J.W. (2015). Pipes at the Ready. Chanter, Summer 2015.

(3) Merryweather, J.W. (2015). Geordie Syme’s Drones? Chanter, Winter 2003, 13-14.

(4) Ibid. ref. 2.

(5) Ibid. ref. 1.

(6) Ibid. ref. 3.

(7)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musette_de_cour

(8) Moulder, J. (2018). Decoration or Function? Chanter, spring 2018.

(9) Wikipedia: Schreger lines are visual artefacts that are evident in the cross-sections of ivory. They are commonly referred to as cross-hatchings, engine turnings, or stacked chevrons.

(10) Stewart, P. (undated). The Life and times of the ‘Lowland’ pipes. http://elearning.thepipingcentre.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/PT38_LowlandPipes.pdf

(11) http://www.thebagpipemuseum.com/MacDougall_Gavin.html

By Calderwood, Ross Merryweather, James Trad

From Chanter Autumn 2019.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!