The Bagpipe Society

Reducing the range of a melody to fit on bagpipes

Everybody who plays the bagpipes knows about its limits in range and, according to the type, the available chromatics. This is no problem as long as you are living in a country with an ongoing tradition of bagpipe-music, if you are interested in a specific bagpipe-style from other countries or if you are simply writing your own music. When I started playing the bagpipes in 1998, most of the dance music played at BalFolk-like events in Germany was French inspired or, if not inspired, then copied from French players.

By accident, my first teacher was one of a few people who had started searching for traditional German repertoire. And that is how I stumbled into the small scene, which has now got quite big over the last few years, that is into German traditional music. Unfortunately, most of the dance music manuscripts you can find in the German archives are written down by violin players, who have to care much less about range and chromatics than pipers. So, as a piper in a session, one has to wait for the few tunes in the manuscripts that are suitable for pipes and go for a beer while all your colleagues are playing all the other stuff …… or you find a way to adapt the existing music for your instrument.

If you go for the first version, it’s very likely that you will be too drunk to play the few tunes fitting on pipes, so it is far better go for the second version and try to adapt tunes by reducing their range so that you can play together with the fiddlers all night through. In this short article, I want to explain how you can go about making tunes fit the range of the pipes.

There are two possibilities I can think of.

1. You can simply play single bars or phrases an octave lower or higher so they become part of the instrument’s range, or,

2. if you have triads, you can possibly change the inversion of the triad.

If you are adapting tunes, take care to keep as much “original substance” of the tune as possible.

Also it might be a good idea to keep an eye at the flow of the melody. If, for example, you have transposed a bar an octave lower there may be big jumps in the melody that are not in the general mood of the original, as well as lowering the fun of playing the tune. You deal with this effect if you not only transpose a phrase, but also adapt the notes around it a bit. A common method is to replace those notes and choose another tone out of the fitting triad to reduce the gap and create a more logical melody line.

I will give you two examples of tunes where I have adapted them. The goal was to make them playable on Säckpipa. To make it clearer, I firstly need to explain about this kind of bagpipe to make sure everybody can understand why I changed the things the way I have. The Säckpipa is a bagpipe with one chanter and one drone and both have single reeds. The drone is playing an “e” which is at the same pitch as the six-finger-note of the chanter. The range of the chanter goes from d’ to e’’ including the following tones:

d’, e’, f#’, g’, g#’, a’, b’, c’’, c#’’, d’’ and e''

For all people who are more into Swedish pipes, I am talking about a chanter using half-closed fingering, including a second thumb hole and a doublehole for major and minor sixth.

1. Here is an example where I transposed parts of a bar an octave lower

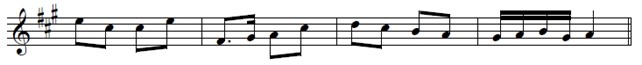

the original section:

and the adapted version

As you can see, after having changed just three notes the tune is easily playable on pipes. As I mentioned earlier, you have to double-check to ensure that the flow of the melody has not changed too much. In fact, you can play the tune as it is after the first change (like I do) but there is the option to make another small change, as you can see here:

Why did I make this change? The first bar given in the example is clearly in A-major. But by transposing the second bar I created a break in the original melody line, so to reduce the gap, I chose another tone out of the A-major triad and replaced the last note of the bar with it - so the ‘e’ at the end of bar one becomes an ‘a’. Now bar one leads again to bar two.

Actually I find it quiet hard to decide which version I prefer. In the original melody there was a big jump at the end of bar two and this got lost when I did the transposition. So, you could say

it might be good to keep the new jump of the first changed version instead. However you decide, both versions will work, because the second change utilized part of the triad which was in the original first bar.

2. Here is another example where I adapted parts of a melody based on triads

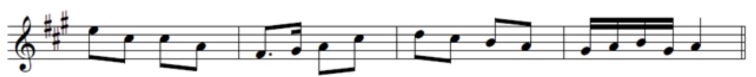

the original section

and the adapted version:

The problem with this tune is the c#’ in the first bar as it’s not playable on Swedish pipes (you remember, the lowest note is d’). In order to keep as much of the original tune as possible I decided against changing the complete first bar by using an inversion of the triad and went for only changing the low c#’. Possible replacements for the low c#’ would be: e’, a’, c#’’ or e’’. Which one to choose becomes easy if you have a closer look to the melody structure of both bars as a unit. In both bars the first three notes are a line downwards, the following notes a line upwards. The goal is to keep this structure as good as possible. Because a’, c#’’ and e’’ would create a jump, the only option is to play another ‘e’ instead of the ‘c#’’.

A special sound effect of the Swedish pipes makes this decision even more logical. Because the drone and the six-finger-note are at the same pitch, you can create the illusion of playing a pause.

If you are now playing this tune together with an instrument that is able to play the original melody, nobody will even recognize that you made a change to it.

That’s all what’s need to be done to make melodies playable. So, have fun in the archives searching for music!

From Chanter Winter 2018.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!