The Bagpipe Society

Piping in Palma: The Fourth International Bagpipe Conference – a delegate's view

There are plenty of reasons to visit Mallorca in March – the gentle breezes from the Mediterranean, the traditional welcome of Mallorcan people, the arrival of the swallows two months before they arrive in northern Europe. The arrival of bagpipers from around the world was yet another; when the International Bagpipe Conference was held, outside the UK for the first time, in Palma, Mallorca, over the weekend of International Bagpipe Day.

The programme looked promising: an opening concert on the Friday night, a day of lectures on Saturday, followed by its perfect antidote, a session in a nearby bar, then a trip out of the city on Sunday for a day of music and rural pursuits. Still, I was anxious to know whether I was the only Briton to make the trip. It was reassuring to find the familiar faces of David Faulkner, who was one of the organising trio, and Chris and Anne Bacon. We were the British contingent, though American Roger Landes, another organiser, was proudly wearing his BagSoc lapel badge.

That the conference delegates were outnumbered by local people at the opening concert gives an indication of the popularity of piping in Mallorca. Cassandre Balosso-Bardin, the third organiser, introduced the acts, flipping gracefully between Castilian, Catalan and English, and established the truly international basis of the gathering. “Bagpipes of the World” was its title. Musically we started in Mallorca, with three colles (bagpipe, whistle and drum duos) who then joined in a single band. Mallorcan pipe music tends to be upbeat, marching or dance music, deceptively easy to listen to, but frequently with a sting in the tail such as a rhythm or speed change. Second on were the ZampogneriAFiumeRapido trio, who played a range of zampognas and other pipes from Italy. The effect of the zampogna’s three chanters is that the harmonies sound improbably rich, and the combination of three players is astounding. In one tune the zampogna played the lower harmonies, with two bombardes skittering above. Their finale was a set of hornpipes as played by Blowzabella. (ZampogneriA will be appearing at the Blowout at the beginning of June.)

After the break came Cem Yaziki, a tulum player from the Black Sea coast of Turkey. The tulum is a single reed, double chanter pipe, with a hornpipe at the end. Melodically I found the music difficult to grasp, but the effect was mesmeric, with constantly shifting chords, and a wall of sound from an unexpected range of notes from so simple a chanter. In many ways it was similar to the zampogna in its complexity of sound. Finally came a trio from Galicia, the Bellón Maceiras duo with Cabi Garcia. Gallego music tends to be dominated by the gaita, often played in close harmony or in massed bands with percussion, often very loudly. In this case a single gaita was accompanied by a button accordion and a guitar, mixed to near equality. So, the accordion provided chords but also rhythm; the three instruments all contributed to harmony, the effect being lyrical rather than fast. They played with unexpected humour, and encored with one of my favourite gallego tunes, San Roque. We left a good concert buzzing with the prospects for the rest of the weekend.

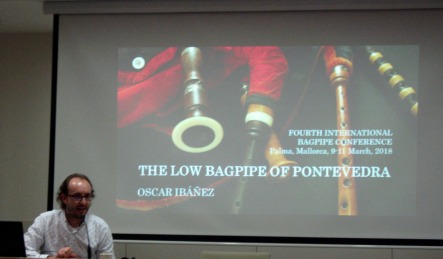

The conference proper occupied most of the Saturday and the conference centre was comfortable and modern. We were greeted in the entrance hall by two xeremiers playing pipes and whistle and drum, though these were silent and huge, being examples of Catalan gegants. Papers were presented on time and in a relaxed fashion, with the IT working well, and simultaneously translated to or from English, Catalan and Castilian. The skill of the two translators in their soundproof box was palpable. The first papers discussed pipes from Romania, Lithuania, Macedonia and Turkey. Each told the now-familiar story of folk instruments dwindling as culture became more 20th-century, then being rescued and revived. Interesting that folklore, initially suppressed by the communist regimes, was later promoted by them. Also that emigration tends to rob countries of younger people, hampering a musical revival. And what about the similarity in names of the gajda of eastern Europe and the gaita of western? Was it that the name derives from Arabic, or that the name migrated from east to west with the Visigoths? Interesting, if unanswered. The Occitan pipe, or bodega (wine-skin), almost died out after World War I but now thrives after reinvention of pipe and shawm bands, and collaboration with other pipers in the Balearics, in Langedoc and Calabria. In Gascony, the boha has been revived after vigorous cataloguing and measuring of surviving instruments, and their easy accessibility on the internet. The Italian müsa had died out, replaced as in France by the accordion, but musical detective work suggests a place for it in duet with the piffaro. There used to be a variety of different Galician gaitas. Around Pontevedra the gaita tumbal had a low chanter in B and high drone at the chanter’s 5th, and a few recordings exist. Thus, different moribund cultures have been recognised as valuable and endangered, and brought back to varying degrees of health. The details of resuscitation vary, but it requires academic study, enthusiasm, and generally collaboration with other cultures.

The most scientific paper, by Cassandre Balosso-Bardin and colleagues, showed what you can investigate about piping technique, given enough resources. Using pipes with audiometric and video recording, pressure and flow sensors, and tracked elbow movements, she showed that breathing, and tuning by pressure on the bag, vary not only for mechanical but also musical reasons, and are more sophisticated in experts than novice players. Not surprising perhaps, but not previously shown, and showing the way for future research.

Then to the left field. Piping as political protest has been around at least since the Jacobites, but is an increasing force in modern protest, as research through social media can reveal. Highland pipes are particularly effective in opposition to so-called hate preachers. In Hong Kong, on the other hand, local membership of pipe bands is thriving, perhaps as a kind of protest against imposed de-colonialisation. Then to piping and mindfulness. Piping while walking the dry-stone mountain paths of the Tramuntana mountains in Mallorca benefits not only the piper, but also the local wildlife, and the sacred forest.

After all that brain-work, what we needed was a damn good session, and that is what we had. We gathered in a nearby bar, stocked with plenty of snacks and beer, and played the evening out. Predictably we divided into camps, mainly dictated by pitch (xeremies are pitched in C#, which discourages collaboration). There was an English camp, with its offshoot from Scotland, and then the Gallician and Mallorcan camps, who clearly won on volume. The Occitans seemed able to collaborate, and that is perhaps how they have thrived. There was ample percussion, able to add power to anything. Then there was the Bulgarian camp. They kept popping up throughout the weekend, a tune to suit every occasion. This evening they came in ethnic white and red shirts, goaty bagpipes and lightning fingers. Fabulous! Eventually, ears and brains ringing, we retreated to our beds.

On Sunday we were hosted by the Xeremiers de Sóller, internationally-recognised pipe band, and one of the longest-established on the island. They played for us on the train ride to Sóller, on the rattly 19th century train originally built to transport the orange and olive crop to Palma, and now lovingly preserved to transport tourists. The train winds up into the mountains, eventually disappearing into tunnels and emerging over the magnificent Sóller valley, the Valley of Oranges. After presentation to the mayor of Sóller, we were entertained by the Xeremiers de Puig de sa Font, another long-established band, who combine xeremies and flabiol with other instruments such as shawm, clarinet and trombone. Then off to the agricultural cooperative. The Sóller valley thrives on olives and citrus fruit, and we were treated to not only learning about them, but generous tasting too. The cooperative had recently taken the decision to use modern production machinery, so it was interesting to contrast their produce with that of Can Det, our next visit, a 400 year old farm producing olive oil by traditional methods. Sóller is a delightful and busy town, but while others continued to explore (and the Bulgarians found a street corner to play), I slunk into a cafe for a cafè amb llet and relax before the return train trip to Palma.

An enjoyable and successful conference indeed. It was well-balanced, with plenty for everyone, and (as far as I was aware) ran smoothly. It was interesting to see not only that ethnomusicologists are studying and reviving ethnic bagpipes, but that scientists find them a fruitful area of study, and that even protest and mindfulness can involve pipes. In particular, it was good to find a group of pleasant and like-minded people and to play pipes and chat with them. I look forward to Boston Massachusetts in 2020.

Addendum and Acknowledgements from Cassandre Balosso-Bardin on behalf of the International Bagpipe Organisation:

The Fourth International Bagpipe Conference was a real success with participants from all over the world, and many from different Spanish regions. However, none of this would have been possible without the help of several key people. First, we would specifically like to thank two people without whom this conference could not have taken place: Toni Torrens and Càndid Trujillo, with their invaluable help, we were able to source venues, companies, sponsors and administrative help that would otherwise have been unreachable. We would like to thank the many different societies, organisations and institutions that supported this event: in the UK the Bagpipe Society and the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society both gave us generous grants and helped us spread the message across the communities. We would like to thank all the organisations and groups in Mallorca who provided facilities, helped with the arrangements and those who organised and funded the trips. We also thank the many volunteers who gave their help willingly. Special thanks go to all the donors who contributed to the crowdfunding campaign to help gather the last of the funds needed for this conference. Finally, I would like to thank the speakers, musicians and delegates for coming and making the three days a real success.

On a final note, we would like to announce that the next International Bagpipe Conference will truly go overseas - to the United States. We will be organising the event in Boston with the collaboration of a local committee. Long Live the Bagpipes!

The International Bagpipe Organisation: Cassandre Balosso-Bardin (President), Roger Landes (Secretary), David Faulkner (Treasurer)

By Balosso-Bardin, Cassandre Bynoe, Jonathan Faulkner, David International Bagpipe Organisation Landes, Roger Trad

From Chanter Summer 2018.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!