The Bagpipe Society

Decoration or Function?

As researchers and instrument makers of historical instruments, Eric and I have to gather information and inspiration from as many sources as possible. In our field of renaissance double reed woodwind instruments, it is fortunate that there are still some extant examples, albeit in museum collections which may or may not have been well cared for over the last few centuries. But we also delve into contemporary accounts and records and there is plenty of iconography out there to help (or hinder!). One gets very skilled at looking at iconography in detail in order to deduce more facts or clues which may help us in understanding how instruments were made and played. However, even with so much available information, reproducing these instruments still requires educated and experienced guess work, coupled with a great deal of trial and error.

With studying bagpipes from the 15th to early 17th centuries, these same issues occur, other than the added problem of there being no surviving originals from this period. Whilst bagpipes are mentioned in a variety of written accounts, on the whole, these tend to be passing references to the instrument resulting in a paucity of fully detailed descriptions. It can therefore be difficult to determine the exact model of bagpipe referred to, how it was tuned or what the range or fingering system was. For example, no-one can ever be 100% certain exactly what a Lincolnshire bagpipe was and what were its defining characteristics.

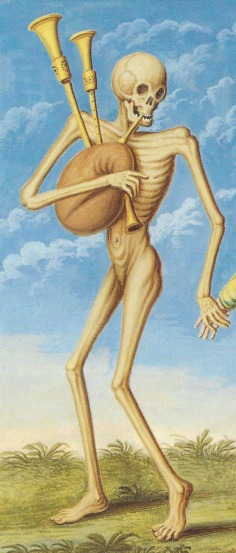

What is clear by studying just some of the surviving bagpipe depictions found in England (see the article on The Bagpipe Map elsewhere in this edition for inspiration) is that there was a wide variety of bagpipes from the medieval and early modern eras. Then, when factoring in the various bagpipe illustrations and carvings from across continental Europe, the range different type of bagpipes is seemingly endless. Now, whilst I am not a bagpipe maker, that doesn’t stop me looking and questioning the different illustrations, trying to understand the instruments and trying to gain some clues about how they could have sounded and how they were played.

It is with my “curious mind” head on that I am puzzled by a particular feature shown time and time again on bagpipe illustrations from the late 15th through to early 17th century in Germany. The feature in question appears on the drone of the bagpipes, where one would expect the tuning slide to be but it looks, to all intents and purposes, like a fontanelle.

As a maker of double reed instruments, I’m very familiar with fontanelles. They appear on the larger sized renaissance wind instruments where lower brass keys are necessary in order to reach the lower tone holes and their purpose is to act as a protector for the keywork underneath. Made from wood, usually with brass ferrules, this thin wooden ‘case’ has holes in it to help with the venting of the tone hole beneath and the fontanelle holes would usually be formed into a decorative pattern. Other than a device for stopping the keywork being damaged they serve no acoustical function.

So why would there be, what appears to be, a fontanelle on a drone? There would certainly be no need of a key cover or protector as keys simply don’t appear on drones. Were these ‘fontanelles’ purely decorative? Why would a maker go to the trouble of making such a device if it wasn’t necessary? As a maker I know that there would be considerable work involved in making a fontanelle and unless necessary, I cannot see why they would be present. My reasoning therefore suggested that perhaps I had misinterpreted the images and they weren’t ‘fontanelles’ after all. I have looked at, studied, re-examined and looked again at the various pictures and each time I go back to them I remain convinced that they are indeed ‘fontanelles’. Over the years, I have also shown them to other bagpipe enthusiasts and makers with the questions: are these fontanelles? If so, why would they be on the drone? The response has always been; “yes, definitely a fontanelle” and “no, I don’t know why”!

Having mulled this issue over for sometime, I was finally prompted to write this article after seeing the wonderful image of a bagpiper depicted on the rear cover of the last edition of Chanter. It was of a 16th century carving of shepherd with his bagpipes in Chartres Cathedral and the drone carries the most perfect example of the type of ‘fontanelle’ I am referring to.

Pictured below are some of the other illustrations that have been puzzling me for years. As a comparison, I show a contemporary illustration of a bagpipe with a more common tuning slide and I think it is clear that there are distinct differences between them.

The only suggestion I have as to the function of these ‘fontantelles’ is that actually they are ‘blind’ and not a typical key cover type after all. The clue is in an instrument that was recreated by the Dutch bagpipe maker, Frans Hattink. Back in 2005 in his home town in the Netherlands, an instrument was excavated from the well of the local castle. It was dated to sometime during the 80 Years War (1568-1648) during which the castle had been destroyed. Initially, it was thought that it was a bagpipe chanter which is why the town approached Frans as they wanted him to make a reconstruction of the instrument so that it could be displayed alongside the original. However, having made it, it was clear to him that it was a small shawm rather than a chanter and this led him to consult with my husband, Eric. One of the most striking features of this instrument is that there is a removable section of the bore on the lower half of the instrument and this takes the form of a ‘blind fontanelle’. This section clearly had a function and was designed to be removed as it had a socket and binding at both ends, but it had no keywork. The decorative hole patterns in the fontanelle were superficial only and they did not go far into the wooden part and certainly not as far as the bore. Frans believed it to be a similar instrument to that depicted by the mid 17th century Flemish artist, Jan Steen. There is also another picture, painted by Evert Collier (1640-1707) which shows the same type of instrument – a small shawm with a fontanelle device but no keywork. Indeed, there is a striking similarity between Frans’s shawm and those in the pictures.

Having made a reproduction of the small shawm, it was clear that the fontanelle did indeed have a purpose. By removing the ‘fontanelle’ section and reassembling the instrument without it, the pitch of the lowest note changed as the overall length of the bore had shortened.

So is this the answer for the ‘fontanelles’ on drones? In the absence of the tuning slide, was the ‘fontanelle’ there to enable the player to change the pitch of the drone by removing it completely? As fontanelles were a familiar decorative device present on other wind instruments at this time, was the device was copied and adapted to suit another function?

Of course, there is another possible answer and that is that the artist got it wrong as is so often the case! Going against this argument is that there are a significantly large number of illustrations of ‘fontanelles’ on drones spread over quite a long time line and also over quite a wide geographical area. The ‘fontanelles’ also appear on a number of different types of bagpipe. Whilst there are pictures of bagpipes with a more typical tuning slide drone shown alongside a pipe with ‘fontanelle’ drones, I have not yet found any examples of an instrument where both types of drone are depicted on the same instrument or where there is a tuning slide and a ‘fontanelle’ on the same drone. For me, this is quite significant, indicating that the ‘fontanelle’ drone is probably accurately depicted.

Without a definitive answer as to the purpose of the ‘fontanelle’ on a drone, and as it continues to puzzle me, I thought I would hand it over to the collective minds of The Bagpipe Society. I welcome all suggestions and look forward to your possible answers.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!