The Bagpipe Society

Bagpipes in Lithuania: From historical facts to modern interpretations

The bagpipe in Lithuania was first mentioned in “The History of Northern Nations” written by Swedish historian Magnus Olaus, printed in 1555. In the same year the pipers (bear trainers) who had to be taxed were mentioned in the letter written by Žygimantas, the Duke of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and in 1565 the instrument was mentioned in the decrees of Vilnius Seimas. In a small dictionary for the translation of Bible (1580) it was written that “pipe is made of horn” or “murenka”, which is translation from the German word “sackpfeife”. Following this, there are several references to the pipes in various documents where it states that the intentions to prohibit its use. The instrument was often being played by wanderers and beggars who used to gather in market squares and this was one of the reasons Catherine II prohibited the use of bagpipes. Consequently, this decree helped influence the extinction of bagpipes.

I should mention that historically the Grand Duchy of Lithuania used to rule a large territory which extended from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and at this time it was one of the biggest countries in Europe. The bagpipes found in the region could be Polish or Ukrainian (Carpathian Mountains), but they survived in the unique form of Labanoras pipe. Today we may see that Byelorussian bagpipe looks the same as Lithuanian but this similarity is related with certain cultural-historical circumstances.

In 1932 Stalin declared that the Republic of Belarus was to be part of the Soviet Union and thereafter bagpipes in its territory suddenly became known as Byelorussian. I have doubts about giving Lithuanian, Byelorussian, French or Scottish nationality to the instrument. Probably, using the name of a territory where the instrument was widespread makes more sense in this case. Whilst today we have expressions like ‘Baltic countries’, we know that there are different instruments in every country and, for example, the Estonian bagpipe is very different from the Latvian, and the Latvian bagpipe is different from the Lithuanian and the other neighbour, Poland, has yet different instruments. Anyway, this seems to be a question for scholars to solve if it is important at all.

The Lithuanian language is very archaic. Our language is the oldest member of the Indo-European Language group and together with Latvian language retained its unique sound and content. Despite many years of Soviet occupation and exile, the Lithuanian language remained and prospered during the last century. Today, there are more than four million Lithuanian speakers in the world and linguistic experts cite it as an example of the oldest language still being used in everyday life. There were many names of pipe (dūda) in Lithuanian, for example: ūkas, maišinė, murenka, kūlinė, kūlinė dūda, labanarska dūda, dūda raginė, Vilniaus dūda, Alvito dūda (bagpipe from particular village or city). Pipe, the use of it and its construction is mentioned in old Lithuanian songs, sayings and dances and special kind of multipart songs. This shows that the instrument was widely used in our lands.

Furthermore, our country is a singing country and we have more than a half of a million songs that were written down. It is interesting that in the old songs which were written down two hundred years ago even the worse moments of human life like death, war and loss are described in diminutives (karužė, mirtužė, bernužis, mergužė). Peaceful and light moods are usually felt in our songs. We have also maintained unique tradition of multipart singing which is called SUTARTINĖS in Lithuanian and is especially characteristic in Lithuanian territory. Sutartinės are included in UNESCO world heritage register and this multipart singing came from ancient pre-Christian times when they formed a part of certain rituals.

It is difficult to say how often instruments were used alongside the voice, but according to some lyrics in songs, for the ritual of visiting the crops, bagpipers were used to accompany singers. Two years ago we found an old multipart song about bagpipes and the lyrics contain words like ”devil in a pipe”, “I travelled all the world but haven’t found a devil anywhere”. The interesting point is that there is no tradition of these songs being performed in churches and devil only gains a negative meaning after Christianity came to our lands. In the old tales the devil is one of the gods (god of the souls) and man tries to co-operate with it.

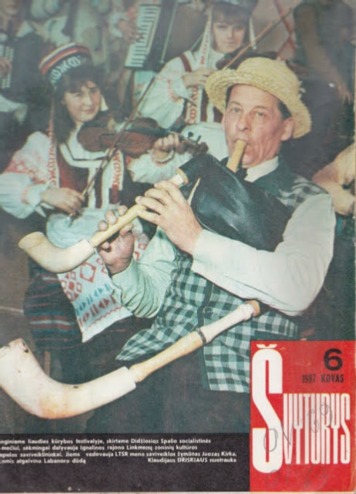

The first recordings of the player Juozas Voldemaras were made in 1908. Later recordings are very rare and only fragmentary but I do think all of them have yet been discovered in the archives as colleagues from Belarus are still finding new recordings of bagpipes. In 1986 the Lithuanian journal “Švyturys” used a photo of bagpiper as a cover. The photo was made after a concert on national TV; but it appears that this recording was probably not kept. However, the son of bagpiper seen in a photo, still has that instrument, but unfortunately it is not in playing condition.

In the church chronicles there is information about bagpipers from Labanoras who used to play pipes during the feasts of Vilnius Kalvarijos. These feasts still take place and there is a ceremony of recreating the ‘Way of the Cross’. During the procession it was customary for a bagpiper to take over when walking up the hill as it was too hard for the singers to walk and sing but nowadays the priest invites a young bagpiper to perform.

There is a lack of information about bagpipes during the Second World War and during the period of Soviet occupation from 1945 to 1990. During the first post-war years the communist regime exiled the most talented people: teachers, doctors, priests, successful farmers and intellectuals to Siberia. The Soviets supported “the art of folk” by professionally distorting reality and selecting works that were considered suitable for their ideology. Several generations of people grew up in that distortion. However, about 1968 more and more students became interested in the old heritage of our country and ethnographic expeditions were organized. The purpose of them was to collect surviving traditions, examples, stories, songs and dances and people formed folk groups to play the traditional folk music. Some people tried to make bagpipes, however, in most cases these attempts were not successful and there were no experienced makers who could make a good-sounding instrument. In 1987, jazz musician, Skirmantas Sasnauskas, got together with a craftsman to successfully constructa bagpipe in 1987 which was then used in jazz compositions. Actually, he made the instrument by himself with some improvisations and he still plays this particular instrument in concert.

I first acquired my own bagpipe in 1999. I bought it from bagpipe master Todar Kažkurevič from Belarus and started playing it in my apartment. Of course my neighbour heard the playing and came to listen… After listening to me he told a story about him visiting Labanoras - a small village in North of Lithuania in 1970. This was the place where he heard “Labanoro dūda” (Labanoras pipe) being played by a priest. This aroused my interest and after some time I went to that village again and started asking local people about that pipe and, after several years, came across the instrument in Švenčionys museum. That was the beginning of my interest in the history of this instrument in Lithuania.

My growing interest was the reason why me and my friend Todar Kažkurevič visited all the museums in Lithuania that had bagpipes. We took pictures of these instruments and measured them. In all we found twelve examples and not all of them were well preserved. We have had many discussions with bagpipe makers about the role of the bagpipe in life today. Our intention was to recreate the instrument which has a place not only in our mythology but also in our rituals. Over time, people started to invite us to play bagpipe at their baptisms, weddings, funerals but the instrument did not find a place in popular music.

However, a breakthrough happened in 2004 when the CD “Silence of Labanoras” was recorded together with Lithuanian jazz star Petras Vyšniauskas. The record was made inside the chimney of 300 year old house which now is a museum of Antanas and Jonas Juškos. The space gave the recording a peculiar sound and special mood to the music. It was a free improvisation based on folk melodies. After the release of this album we were asked to perform in some of Lithuania’s largest citing, including the international festival “Kaunas Jazz”, a member of the Europe Jazz Network and a concert venue which is highly valued jazz stars from all around the world. This was strange music but more and more people wanted to start playing bagpipes.

For seven years Todar Kažkurevič made bagpipes and it was his only source of income at this time. However, there are not many that many players who are interested enough in the instrument and it required dedication and effort to play it properly. There are now some new craftsmen who are trying to make instrument, but as yet the results are not very promising. In Lithuania some musicians play Latvian bagpipes, but in general people who want to play pipes play instruments supplied by makers from Belarus such as Dzianis Sukhi and Todar Kažkurevič. They create instruments based on museum examples whilst adding their own improvements in construction and materials and they also have to consider which pitch to make the instrument in. Bagpipes in either D or G with one or three drones (bourdons) are the most popular today and play with a fully closed fingering system. However, in the old recording we hear musicians playing pipes pitched in A .

In 2008 I invited bagpipers from Lithuania to the the first gathering of pipers. It is difficult to translate the title of this event; we call it SUSIPŪTIMAS in Lithuanian but in English it would be something like “blowing together”. This unusual event is like a festival for bagpipers: participants listen to each other playing and share their experiences. If there is a possibility, I invite bagpipe makers from Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Slovakia, Sweden, and Croatia. The makers talk about their instruments and demonstrate how they tune them and play their traditional music. We also organize two public concerts for the audience. (This format will sound vaguely familiar to participants of the Blowout! Editor)

As Lithuanian bagpiping was on the edge of extinction, these are the methods being employed to try and raise interest amongst the people, restore the traditions and develop musical taste. Today there are more than one hundred instruments in Lithuania, however, not all of them are in a proper condition to be played. Music of bagpipes is now often performed on radio and can be heard during various ceremonies and festivals.

Gvidas Kovėra has been working for various Lithuanian TV companies for twenty years as a cameraman, cinematographer and creator of TV broadcasts. Some of his productions have been nominated and won TV awards in the fields of culture, art and entertainment. He also worked as professional photographer and has exhibited in Lithuania and Norway. He has also organized expeditions to Pamir, Andes, Himalayas, Tian Shan and other mountains since 1989 and he has made documentaries of these expeditions. He plays traditional Lithuanian folk as well as improvisational music and is a member of the group “Vilko pupos”, he has also run a number of projects with folk singers (“Lyla” with Veronika Povilionienė) and jazz musicians (project “Tylos Labanoro” with Petras Vyšniauskas). Gvidas also promotes bagpipes and the music of Lithuania by organizing the gathering of bagpipers and spreading information about this instrument on his website www.dudmaisis.lt

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!