The Bagpipe Society

The Maltese Żaqq

Introduction

The Maltese żaqq is one of the most distinctive ‘European’ bagpipes but also one of the rarest and least well known. Even in Malta many people have never heard of it. The żaqq is one of a number of so-called ‘primitive’ mouth-blown bagpipes found around the Mediterranean, in North Africa and the Near East. They all have parallel double-pipe chanters made of cane and fitted with single reeds. They include the Aegean tsamboúna, Cretan askomadura, Turkish tulum, Tunisian/Algerian mezwed, and the Libyan zukra1. All these bagpipes use bags made out of an animal skin but what makes the żaqq unique is the form of the bag; it consists of an entire animal skin, complete with legs and tail: only the head is missing. When held horizontally under the arm, upside down with the legs sticking up, the żaqq presents an amazing sight. Goats, still-born calves, dogs and even large cats were used for bags in the past. The bag is used hairy side out, in common with some other bagpipes found in Eastern Europe.

Historical accounts

When I began my research on the żaqq over 40 years ago, little was known about the instrument outside the communities in Malta where it was played. Anthony Baines2 made only brief reference to it in his monograph on bagpipes and used the name zampogna or zapp, based on an article in Piping and Dancing (1939)3, but these names were not correct. He was aware of a specimen held in the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York which was collected in Malta in the late 1800s. However, desk research subsequently turned up earlier accounts by visitors to Malta of bagpipe playing.

The Reverend Andrew Bigelow of Boston USA encountered a mendicant piper while staying in Valletta in 1827 and wrote about a busker who passed daily under his window4:

‘…he has made a bagpipe of the strangest form and materials, but for all the purposes of sound, it is as good an instrument of the sort as I have ever heard. The bag is the complete skin of a large dog, exhibiting- besides the body - the appliances of head, legs and tail to boot. A bullock’s horn is fitted to the mouth and punched with the requisite number of holes for playing. The big end is outwards, and the horn closed at that part. A small pipe is inserted into one of the forepaws, and with this the performer fills the machine. He carries the thing under the left arm, belly up, and so carefully has the shape of the animal been preserved that it looks for all the world like a live dog, or a wild mountain cat, squeaking in new and strange sound. The oddity of the contrivance and the skill of the musician are sure to attract attention, and before the fellow has gone the length of a street his drone and his twang seldom fail of being stopped by the toss of a few coppers which he hastes to pick up.’’

What a pity that video or sound recording and photography had not then been invented!

In 1838 another writer, the Rev G.P. Badger, who lived in Malta, described the żaqq as the most esteemed Maltese folk instrument and he noted the use of dog-skins for bags5. Bagpipers also feature in old paintings and lithographs dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, and these usually depict a żaqq-player in the company of dancers or other musicians. The żaqq was traditionally accompanied by the tambourine (tanbur) and the friction drum (rabbaba or żavżava). A selection of old illustrations of traditional musicians is to be found in a recent work on Maltese musical instruments by Anna Borg Cardona6.

Field Research 1971-73

The opportunity to investigate the status of the żaqq arose in 1971 when my parents took up residence in Malta. I was, at that stage, a zoology student at Trinity College Dublin and had been interested in bagpipes for a number of years. I was in a pipe band at school and used to busk with the pipes in European cities during my school and university holidays. At Trinity I took up the uilleann pipes and became friends with one of my lecturers, an Englishman – Dr Frank Jeal. Frank played the piano accordion and we shared a common love of traditional music. When Frank learned I was going to Malta in late 1971 he looked up Baines and said I should find out about the little-known Maltese bagpipe. I took up his suggestion and so began a quest which has absorbed me ever since. After making three visits to Malta, the last with Frank, and also carrying out a great deal of desk research we jointly published the first comprehensive study on the żaqq in the Galpin Society Journal in 19777. Musical transcriptions were provided by ethnomusicologist Peter Cooke.

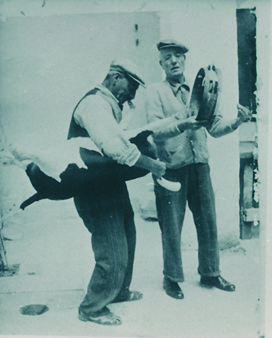

In 1971 there was only one active żaqq player left in Malta – a 55 year old man called Toni Cachia (nickname Il-Ħammarun) from the village of Naxxar. Toni had learned to play as a young man at a time when żaqq-playing was thriving, especially on the streets of Naxxar and in the neighbouring town of Mosta. He was good with his hands and over the years became skilled at making żaqqs and, crucially, fitting reeds and getting the chanter pipes properly tuned. In the last years of the local street-playing tradition, many of the local musicians became dependent on him for their reeds. Toni, as it turned out, played an important part in the survival of the instrument. In the last decade of his life – he died in 2004 aged 878 - he witnessed an upsurge of interest in the żaqq and became something of a national celebrity, appearing in television interviews and documentaries. He was able to pass on the basics of instrument-making and playing to a younger generation and several of them took up the challenge of keeping żaqq-playing alive.

When I first went to see Toni, in December 1971, there was no-one else interested in the żaqq locally, although Malta had an active Scots pipe band. Żaqq-playing was just not fashionable and was regarded by younger people as a thing of the past. In some ways, the crude appearance of the instrument was seen as an embarrassment, and still is! However, as an outsider I had no such reservations and so I got Toni to make me a żaqq using a skin I obtained from the local abattoir. By the time I left Malta after Christmas I had a working żaqq with me. Back in Dublin I taught myself how to play it and when I returned to Malta the following year I took it with me and used it in field research.

Żaqq made by Toni Cachia and used for fieldwork in Malta 1971-73

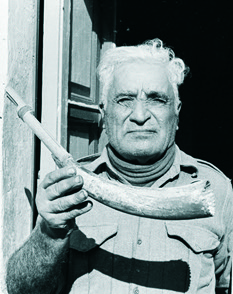

This instrument is somewhat atypical in having a bag made from a nanny goat whose back legs were missing and the stumps tied in a bunch. The chanter was of lead piping rather than cane and the beautifully curved horn was said to have come from a Maltese Ox (the Gendus) which is now a rare breed. The horn is decorated with a brass cap badge belonging to the Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment). This żaqq is now in the possession of the National Archives of Malta in Rabat. Toni Cachia was not afraid to experiment and made żaqq chanters of stainless steel, copper and brass tubing, as well as lead. His favourite chanter was made of brass tubing he obtained from a German aircraft shot down in Malta during World War II.

Back in Malta I began making further enquiries about the whereabouts of former żaqq players, those that used to play but were no longer active. I got the names of seven men, all of them elderly, and began tracking them down. Four of them were too old to play and were out of practice. However, the other three, having overcome their initial reluctance, were still able to play, even though my instrument was unfamiliar to them.

The best player was 69-year old Lażżru Camilleri (Il-Lass) from Mosta, an ex gunner and veteran of World War II who had served in for 32 years in the Royal Malta Artillery. Despite the bag and blowpipe being on the wrong side for him he managed to play my żaqq quite well and I made an 11 minute recording of him on cassette tape. His style and melodic variation was more complex than that of Toni and provided a unique insight into how żaqq music might have sounded in the past.

Another elderly man living in Birgu (Awsonju Bugeja Tal-Grixti) had a different style and again I managed to obtain a good recording of him playing.

Żaqq Music (incorporating analytical data by Peter Cooke)

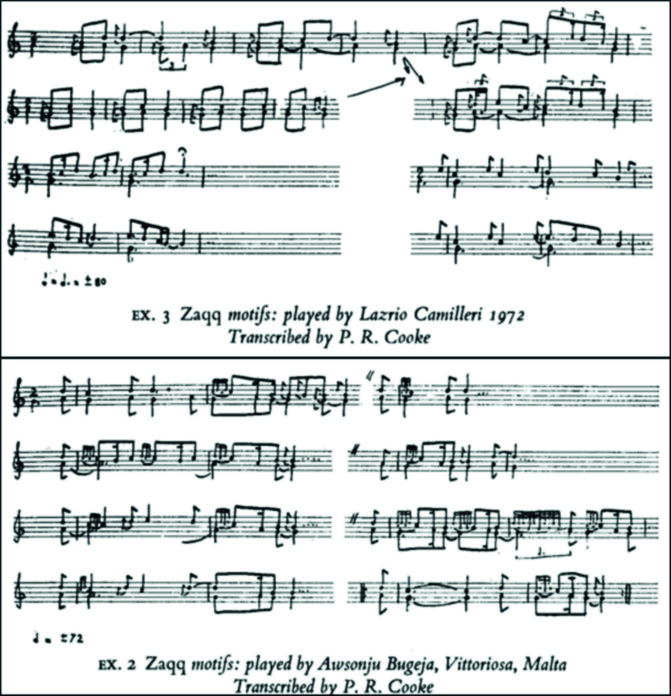

The hole arrangement in the żaqq chanter is usually L5 R1(V)9 although R5 L1(V) also occurs. Fingering can vary but the right hand is always held below the left. Hole LV is never fingered and remains uncovered at all times. The pitch of different instrument varies according to reed and chanter size. The żaqq was never played – at least in living memory – with anything other than percussion instruments and therefore only had to be in tune with itself. Older chanters were smaller with a narrower bore and are likely therefore to have been higher pitched. A tuning fork (oscillator) was used to ascertain pitches during recording of a performance by Toni Cachia. The lowest note sounded by the drone was approximately G (391cps) when covered and A (449cps) when open. The melody pipe notes are A, B (490cps), C (536cps) D (587cps) and E (653 cps). The scale of the instrument is hexatonic which is only roughly diatonic.

The music played is usually in duple time, most often compound duple (6/8), and is clearly music for dancing or processional movement. It has no fixed structure or length and resembles East European and Near East musical styles. Traditionally, each player had his own stock of motifs which he repeated and combined in various ways throughout the performance. Grace notes and cuttings were widely used. The ‘natural’ major third G-B is used consistently in the melodic structure as the point of repose at the end of every phrase. The chord G-D is also widely used. Whereas the main impression given is that of single melody over single drone (G) both Camilleri and Bugeja contrived to give the effect of two voices by using the A drone note. The cadence chord is always the sweetly consonant major third G-B.

The different styles and repertoire of motifs exhibited by the older players provides evidence of the decay in the tradition. The youngest player (Cachia) had a more western sounding style and less variation in his music than the older men (Camilleri and Bugeja) whose styles were more complex and with ornamentation used that was more reminiscent of Arabic music.

Current Status of the Żaqq

Against all odds the Maltese żaqq has survived into the 21st century but it still leads a precarious existence. At this time there are only about six or seven people playing the instrument regularly. These include some of the original members of a local folk group called Etnika10 which was founded in 2000, namely – Ġużi Gatt, Andrew Alamango and Ruben Zahra. Also Edmond Jackson, his son Anderson and Francesco Sultana. The żaqq has achieved a greater degree of recognition in recent years and is no longer the preserve of villagers. Indeed, most of the new players come from the middle classes. Ruben Zahra’s playing of the żaqq in a performance by the Malta Philharmonic Orchestra, in 201111, is a testament to the elevated status of the instrument in Maltese society. Ruben teaches local schoolchildren about Maltese folk instruments but is frustrated by the lack of support in obtaining instruments and promoting an interest in local musical traditions.

Although the żaqq is a ‘simple’ bagpipe, making an instrument is a tricky and time-consuming, and I can say that from personal experience! In Malta it is now difficult to obtain an animal skin or a bull’s horn due to restrictions imposed by animal health regulations and the demise of local butchers. For many years Ġużi Gatt, who learned the trade from Toni Cachia, was one of the few individuals able to make a żaqq from start to finish, but even he had difficulties making and tuning reeds. As all pipers know, reed-making is a skill requiring a lot of patience, to which few are suited. In the case of the żaqq one must not only produce a pair of reeds but also get them playing well together. After Toni Cachia died Ġużi was the only person making żaqqs and he made countless instruments over the past 15 years, before his recent retirement. He made it his mission over the years to promote Maltese folk instruments and generate interest amongst the public. Malta has no professional pipe makers and the would-be piper is therefore dependent on the goodwill of individuals like him if they wish to acquire an instrument.

There is one other man who deserves more recognition for keeping the playing tradition alive and that is Edmond Jackson, son of an Irishman who was a piper and who came to Malta with the Royal Irish Fusiliers. Edmond plays both the Scots Pipes and the żaqq having met Toni Cachia in the late 1990s and learned how to make and play one. Jackson’s Zaqq U Tanbur Folk Group has been going since then and comprises family members, including his son Anderson who is adept on both instruments. The group performs at private functions, in schools and at village festas.

One bright hope for the future is Francesco Sultana, a young man from Rabat who has learned how to make reed and cane woodwind instruments and get them playing well12. He makes Maltese cane whistles (flejguta) and also reedpipes (zummara), the latter based on a reconstruction of what they were thought to have looked like in the past.13 He has made his own żaqq, with the help of Ġużi Gatt, and after experimenting with various chanter configurations has settled for a six-holed melody pipe which he says produces a brighter sound as well more flexibility. He played this instrument for the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh when they visited Malta in November 2015. Francesco plays not only żaqq but also clarinet, guitar and percussion instruments. He believes a new role has to be forged for the żaqq and that the instrument must undergo a re-birth as there is no wealth of tradition on which to build and the continuity has been almost totally lost.

To conclude, reflecting on our experience in documenting the żaqq tradition of the past we were fortunate to catch the very tail end of żaqq playing as it was and to record the music of the last village street-players. We captured only fragments of a lost tradition but this, nevertheless, provides an insight into the richness and playing skills of musicians that are long since gone. The recordings provide a resource that could be used to revitalise old styles of playing, but they probably never will be. The music produced by modern players, including myself, is but a shadow of what was played in the past. We must now look to the future and help forge a new role for the żaqq in the modern world. This is a fine instrument which is unique to Malta and is worthy of support. Funding is badly needed in order to overcome the bottlenecks of instrument supply and to develop more widely skills in bag- and reed-making, tuning and playing. Above all, we need to broaden the żaqq’s appeal and make żaqq-playing as fashionable in Malta as piping is in other traditions.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to Professor Frank Jeal, without whom this project would never have begun. This article draws on material published in our original Galpin Society paper of 1977. Thanks also to my late parents Gordon and Mary; and to all the musicians in Malta and their families, especially the late Toni Cachia. Also, to Peter Cooke for his skilful transcriptions and notes on żaqq music. People in Malta, especially Ġużi Gatt, Ruben Zahra, Edmond Jackson, Francesco Sultana, Anna Borg Cardona, Dr Philip Ciantar, Juan Correa, Fernando Benito Saico, the late Ġużè Cassar Pullicino and a host of others, have helped in various ways, in particular Steve Borġ who reawakened our interest in the żaqq when he contacted us in 2011. Taxidermist David Irwin and pipe-maker Robbie Hughes helped me make a new żaqq. Danny Diamond of the Irish Traditional Music Archive kindly digitised the recorded music. Finally, my heartfelt thanks are due to Dr Charles Farrugia of the National Archives and his staff who have gone out of their way to assist me with further research.

Note on Conservation of instruments, music recordings, photos and field notes

After the publication of our paper in 1977 Frank Jeal and I wondered what to do with the żaqq purchased from Toni, and also another żaqq chanter and horn recovered from Mosta żaqq player Pawlu Gatt (iż-Żubin). In 2011 we became aware of the existence of the National Archives of Malta (NAM), which was formally constituted by Act of Parliament in 2005. In 2013 we delivered a lecture on our historic żaqq work and donated the żaqqs in our possession to the NAM and also our field notes, photographs, correspondence and other material relating to our research14. We still had the cassette tapes containing the original music recordings. These were kindly digitised for us by of the Irish Traditional Music Archive in Dublin and are also lodged at the NAM. I am currently working on a żaqq memoir which is due to be published by the NAM in the next year or so. (Email: karlpartridge@btopenworld.com)

All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated.

1 See Van Hees J-P. 2014. Cornemuses, Un Infini Sonore. Coop Breizh, Kerangwenn. 415 pp. 2 Baines, A. 1960. Bagpipes. Occasional Papers on Technology, 9. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. 140 pp. 3 Anonymous. 1939. The Maltese Zapp. Piping and Dancing, Ardrossan. 4(9):1-2. 4 Bigelow A. 1831. Travels in Malta and Sicily with sketches of Gibraltar in 1827. Carter, Hendee & Babcock. Boston. 528 pp. see pp 178-179, 194 5 Badger G.P. 1838. Description of Malta and Gozo. Malta. 375 pp. 6 Borg Cardona, A. 2014. Musical Instruments of the Maltese Islands; History, Folkways and Traditions. Fondazzjoni Patrimonu Malti, Malta. 291 pp. 7 Partridge J.K and Jeal F. 1977. The Maltese Zaqq. Galpin Society Journal 30; 112-144. 8 Borg Cardona A. 2004. Last of the Maltese bagpipers. Galpin Society Newsletter 10, 5-6. 9 Using Baines (1960) terminology. 10 For more information on Etnika see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etnika 11 Bagpipe & Orchestra “Pastorale Pastiche” by Ruben Zahra: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k8SRoUI10pY 12 See Strumenti Tradizzjonali Maltin Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/strumentimaltin/ 13 See Zahra R. 2006. A Guide to Maltese Folk Music (ed Steve Borġ). PBS Malta and Soundscapes. 63 pp. 14 Anonymous. 2013. Maltese folk instrument iż-żaqq. The National Archives Newsletter, No 17, Nov 2013, p 5. National Archives of Malta, Rabat.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!