The Bagpipe Society

The Edinburgh Müsa - Part II

The Edinburgh müsa is a wonderful instrument. There’s a reason why I have dedicated much attention to: it is probably the best surviving exemplar of this type of bagpipe which is specific to a small region in Northern Italy called “Quattro Province”. Fine moduloSo, it was a truly exciting opportunity to see it, measure it, and make a comparison with her ‘sisters’ in Italy. Without exception, the Edinburgh instrument shows all the distinctive features which single the müsa out from all other bagpipes – and these are summarised at the end of the article. The only drawback is that we know nothing of its musical story: the player, or the players, who held it. Neither the places, villages or feasts where its sound was heard. It is a mystery which will continue.

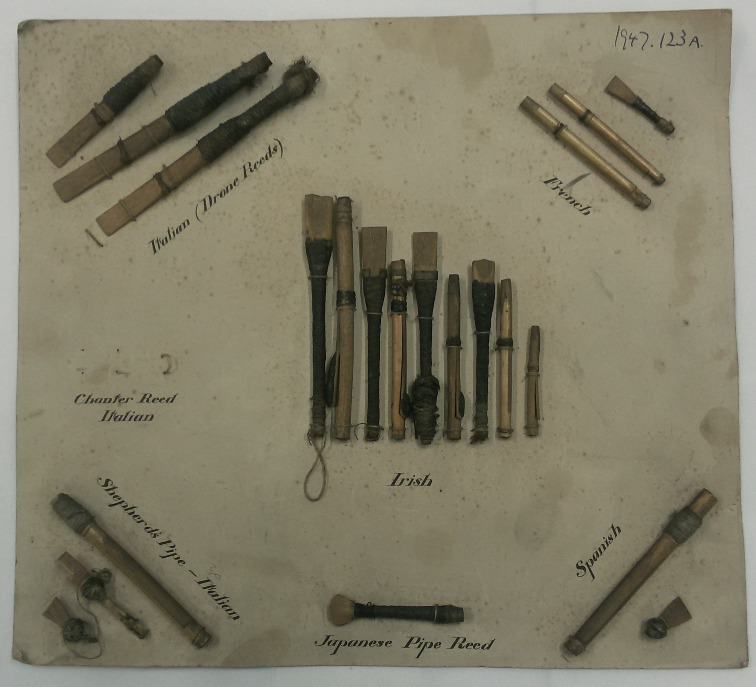

One of the most remarkable features of this instrument is that Alexander Fraser, the person who owned and catalogued the pipes in early 20th century, kept the original reeds. They lie on a cardboard display, under a tagline saying Shepherd’s Pipe – Italian, alongside more reeds from other instruments in the same collection: a zampogna, a gaita, a set of uilleann pipes, a french musette and the reed of an unidentified Japanese instrument. On the left, there is an empty space for a reed described as “chanter reed – Italian” that is - unfortunately - missing. Not surprisingly, the set of reeds for the uilleann pipes is by far the richest of all!

Coming to the müsa reed set, we have: the drone single reed (100 mm long), the chanter double reed, and a spare chanter reed still fixed on a small bone mandrel. The mandrel was used to hold it for the final scraping at the end of the reed making process. This method is still used by piffero players today but the mandrels are now made of metal instead of bone. Anthony Baines was aware of this method, which is common to many other double reed instruments, where the two cane tongues are held together by hemp at the base but not tied onto staple, such as a bassoon. (see BAINES 1960, p. 109 - cited on previous issue of Chanter). The brass staple is fitted to the top of the chanter, by the means of a pirouette (on the piffero) or, on the müsa, just hemp twisted on the tube itself. The reed staple in the müsa isn’t conical as in many kinds of bagpipe, but cylindrical, and quite large indeed (9 mm).

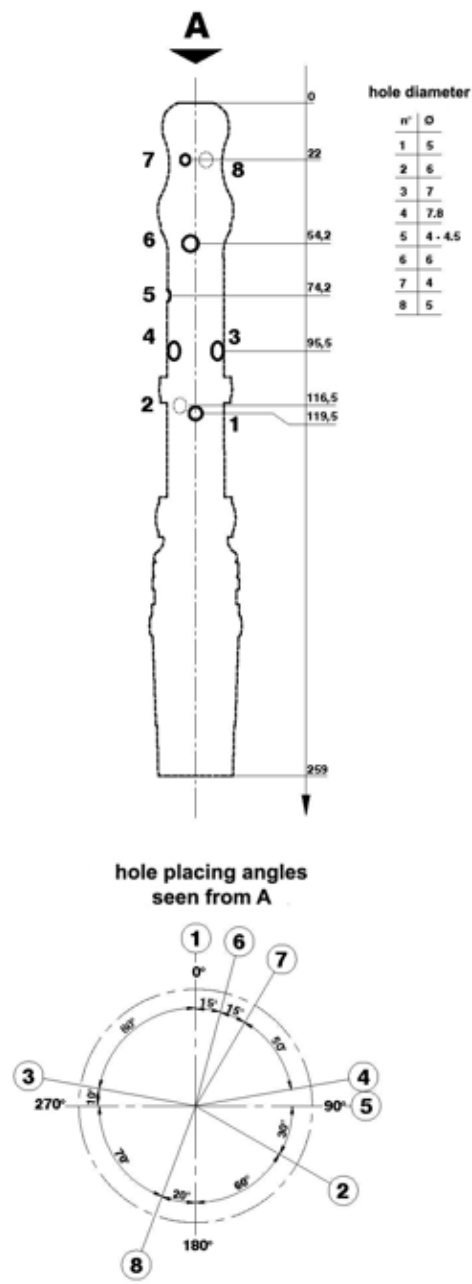

The chanter has 7 finger holes and none on the back. The bottom hand little finger hole is doubled and the left one is still closed with wax, meaning that the last player who used this instrument was right-handed. Next to the bell we have two side holes of the same size, one facing the other. They are often called in Italian ‘orecchie’ (ears) because of their transversal position. Finally, there are two more tuning holes on the front side, between the finger holes and the ears. Normally, in this place, there would only be one hole. I can’t rule out that the top one is a later addition by some player, with the attempt to correct the tuning of the leading-note.

This is not the only example of this: there are more müse showing two holes instead of one in that position: an instrument in the Museo Guatelli, catalogue number A 13 (100-106) even has three holes instead of one. The presence of these holes and the similarity in the overall look of the müsa aroused my interest in this particular instrument: the supposition that it could be from the same hand of the Fraser’s müsa, would be an intriguing idea. But it turned out wrong after more accurate analysis.

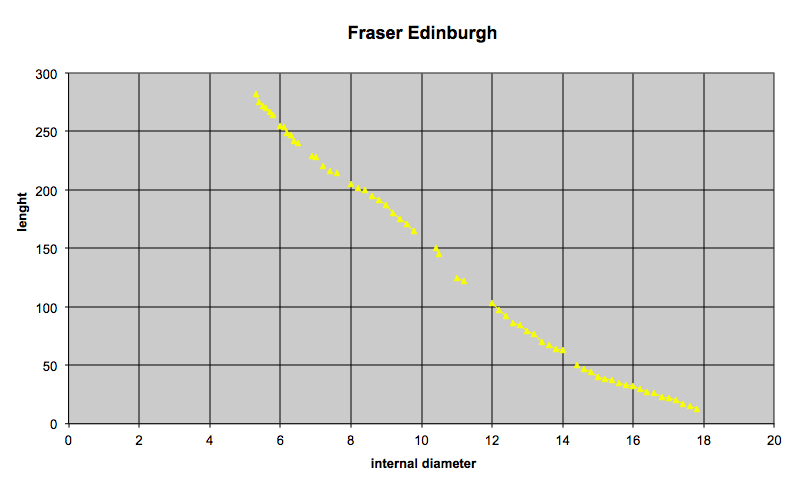

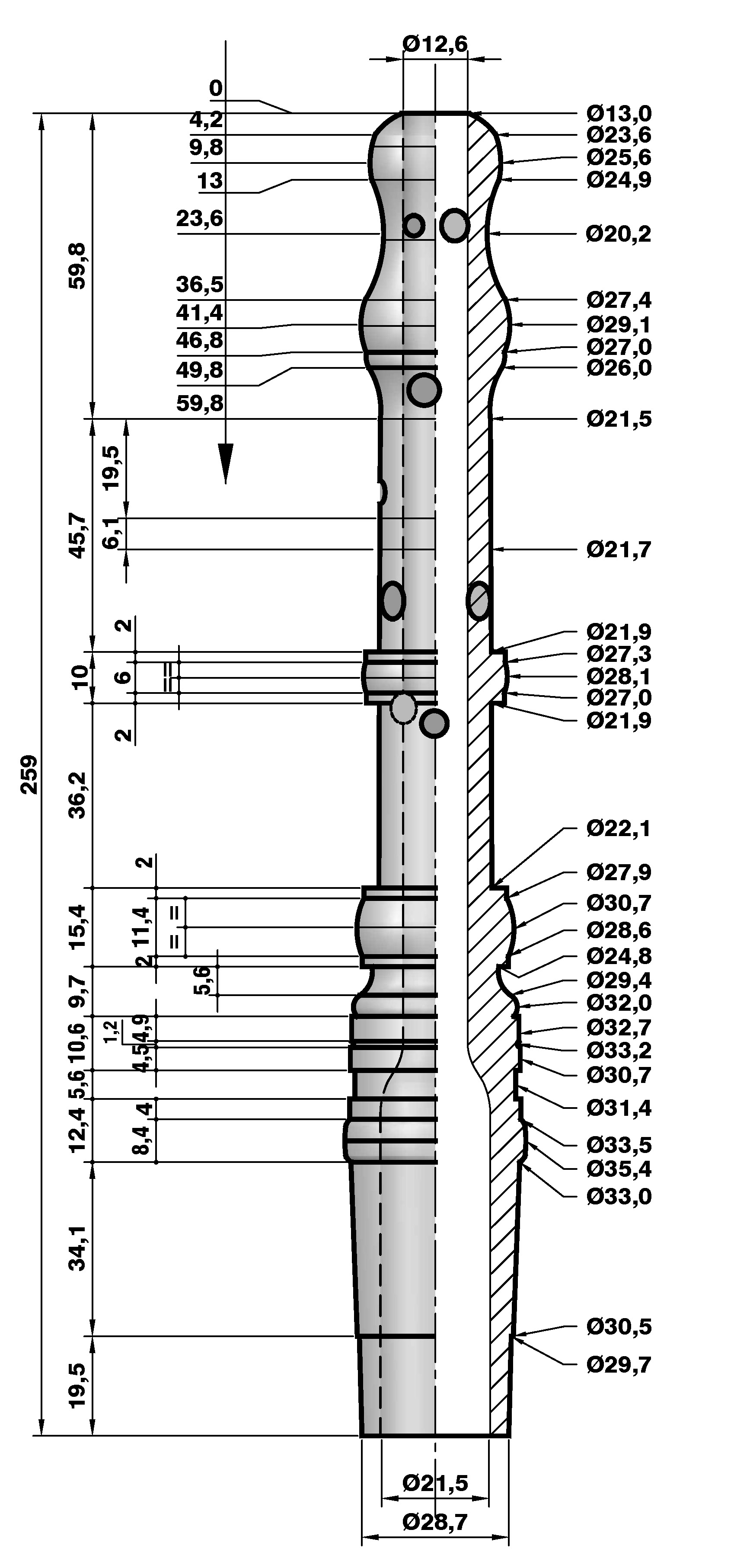

To find out, I compared the bore measurements with all the other surviving müse. The premise being that if there is a strong similarity in the chanter’s bore, then the two instruments could come from the same maker’s workshop as they would probably have been made using the same reamer. Then, I found the only instrument that shows analogy in the bore and in its overall look is a müsa found in Montoggio near Genova, that belonged to Angelo Vaggè “Langin” (1849-1936). It has been measured by Valter Biella in 2012 and the plan is available online: http://bit.ly/Chanter8 As can be seen in this plan, the Langin’s müsa still has the drone reed, and it is considerably longer than the Edinburgh one at 155mm. There is also another point to note: the deep hollows on the finger holes, especially in the right hand ones. It may look as though they have been worn due to frequent playing, but as far as I can tell, so deep an indentation of the wood cannot be result of everyday use only; I suppose that it has been made using some tool. In fact, on the back of the chanter there’s a tiny hollow, precisely where the right hand thumb lays; and this, was probably produced by use (I can’t see any reason to make it on purpose), and it is is much shallower that the front ones. The top hand scallops are very shallow and less than those for the lower hand. If they had been made by use, then I would expect them to show equal “wear”.

Anyway, as it always happens when analysing old instruments, we must be as prudent as we can when coming to conclusions, so I can’t really say if the scallops are work of the original maker, or a later alteration.

Fraser and Baines both suggest that Edinburgh instrument is made from walnut. I agree with their conclusion if we consider the sounding parts, but the stocks are made in a softer wood. They are also turned in a more rustic way when compared with the rest of the instrument. I think they may not be original. In Italy, there are many surviving chanters and drones and they have, at some time in their past, been put together with the addition of new stocks and bags. Therefore, we have many original pipes lacking bag and stocks, or with roughly made stocks, often carved by knife, as in the Guatelli müsa (A13) we talked of before.

The blowpipe seems original, even if at a closer look the quality of timber appears to be different than the chanter’s. The blowpipe has a typical “wicker bottle” shape, peculiar to the müsa, found in all the surviving original examples. On the end a non-return valve, a leather disc fixed with a nail, is still present (see photo on Chanter’s last issue, Autumn 2016).

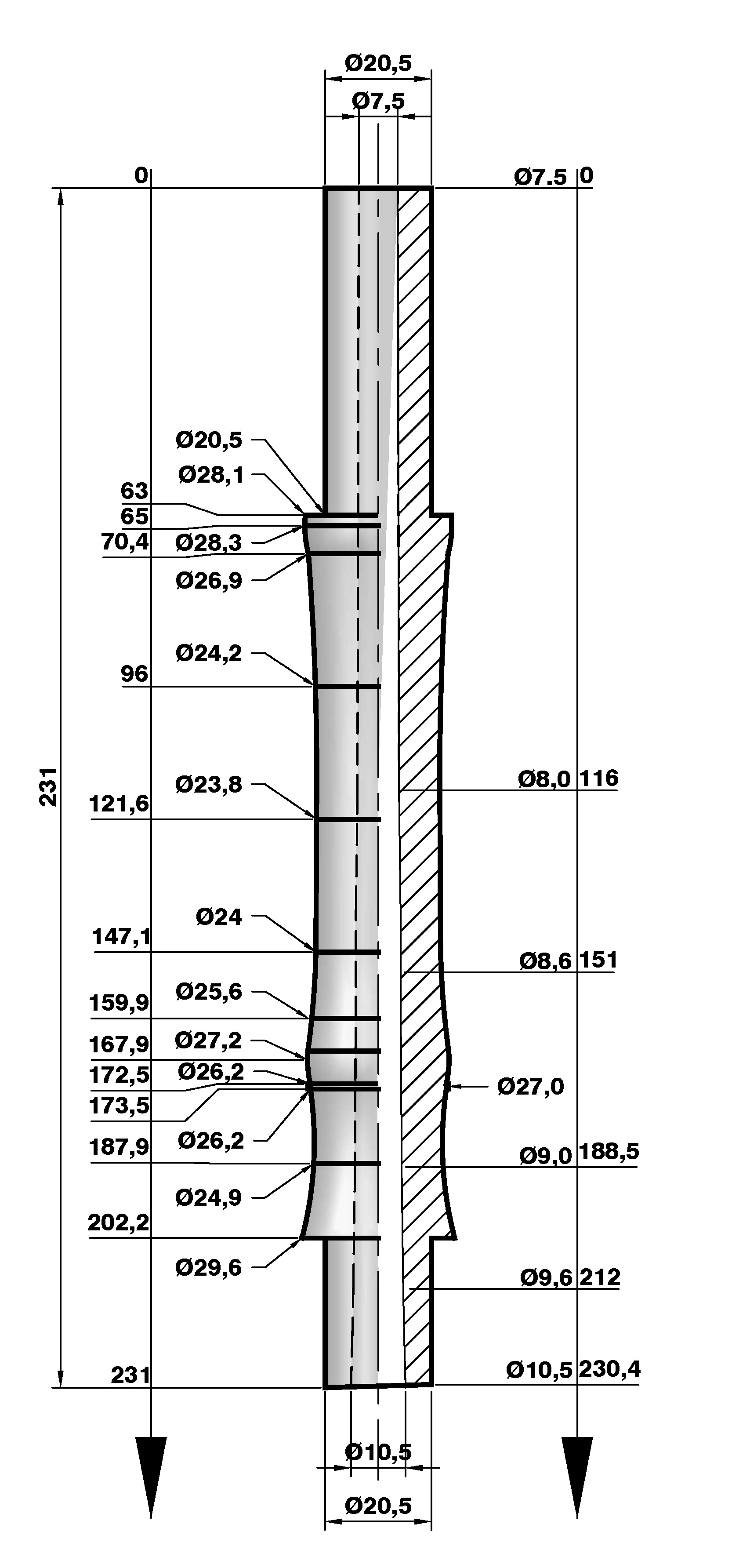

The drone’s first section is plain turned, with almost no adornment. The end section shows a more refined look (precisely as in Langin’s müsa). At the base of the drone there is a big brass ring; it may have been for decorative purposes only, or it could have been added later for more solidity, considering that the piece shows a long crack and has been repaired with glue at some time in the past. On the bell end, a brass wire has been twisted around the wood, presumably for the same reason. Both sections have a really wide bore, over 10mm as often it is in early müse.

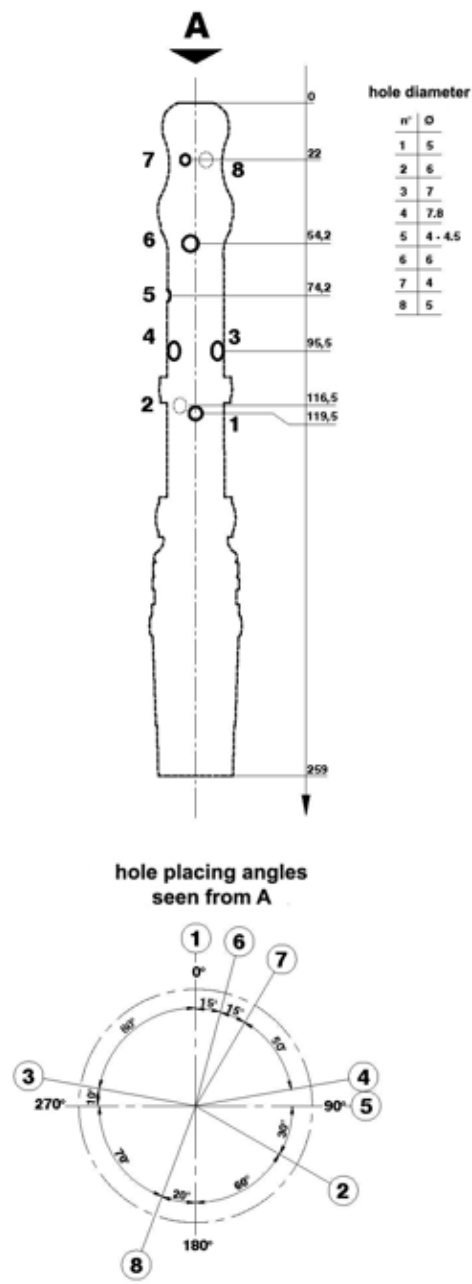

Let’s pay attention now to the holes. In any müsa drone we have holes on the drone’s second section. There are no standard number and position and the original instruments show a wide variety. The Edinburgh müsa has eight. I’m not sure if they are all original but some of them could have been made on a later time: note that the four middle holes are very crude, though the end ones are better made. The holes are not placed in a symmetrical way but with random-like angles (see drawing). All of them are closed with beeswax with the exception of the last one on the bell-side.

It was not possible to separate the two drone sections as they were stuck together very tightly, meaning that I couldn’t measure with any precision the length of the mortice of the drone end section. I had wanted to find the precise point where the bore starts to narrow. That’s why this measure is not reported in the drawing.

It was the same with the brass tube where the reed is inserted; it was tightly fixed, with a wide hemp tenon, in its seat in the top of the chanter. So, I was unable to check the reed seat length. Finally, the holes on the drone are closed with wax, but it was possible to measure them, with just a bit of approximation.

In conclusion I will mention some peculiar features of the müsa, which are without exception, to be found on the example in Edinburgh.

- the chanter has 7 finger holes, no hole in the back. There is one drone only, that is tuned on the dominant note, not on the tonic.

- there are always holes on the second section of the drone (usually 4 to 8 ones).

- the chanter double reed is made on its own and not fixed onto a brass staple.i

- the blowpipe is short and has a distinctive rounded shape.

- the bag is made with a whole sheep or goat skin (hair surface inside), the chanter is fitted to the head end, drone and blowpipe to the upper legs.

- the bag is covered with a fabric lining.

In modern instruments this archaic feature has been abandoned, the reeds used today being made in a more conventional way with cane-blades fixed on a tube. Moreover, the staple is now conical rather than cylindrical.

Thanks to: Rubina Barbieri, Matteo Burrone, Luigi Fazzo, Ferdinando Gatti, Julian Goodacre, Bruno Grulli, Stephen Jackson, Stefano Valla, Marzio Venuti Mazzi.

Daniele Bicego is a maker and player from Milan, Italy. Alongside müsa, Daniele is a maker of uilleann pipes. Find out more from visiting: http://www.danbic.com/

Resources

Chanter Bore

| Diameter | Length |

|---|---|

| 5,3 | 282 |

| 5,4 | 275 |

| 5,5 | 272 |

| 5,6 | 270 |

| 5,7 | 267 |

| 5,8 | 264 |

| 5,9 | |

| 6 | 255 |

| 6,1 | 254 |

| 6,2 | 249 |

| 6,3 | 247 |

| 6,4 | 242 |

| 6,5 | 240 |

| 6,6 | |

| 6,7 | |

| 6,8 | |

| 6,9 | 229 |

| 7 | 228 |

| 7,1 | |

| 7,2 | 220 |

| 7,3 | |

| 7,4 | 216 |

| 7,5 | |

| 7,6 | 214 |

| 7,7 | |

| 7,8 | |

| 7,9 | |

| 8 | 205 |

| 8,1 | |

| 8,2 | 202 |

| 8,3 | |

| 8,4 | 200 |

| 8,5 | |

| 8,6 | 195 |

| 8,8 | 191 |

| 9 | 187 |

| 9,2 | 180 |

| 9,4 | 175 |

| 9,6 | 171 |

| 9,8 | 165 |

| 10 | |

| 10,2 | |

| 10,4 | 150 |

| 10,5 | 145 |

| 10,6 | |

| 10,8 | |

| 11 | 125 |

| 11,2 | 122 |

| 11,4 | |

| 11,5 | |

| 11,6 | |

| 11,8 | |

| 12 | 103 |

| 12,2 | 97 |

| 12,4 | 92 |

| 12,5 | |

| 12,6 | 86 |

| 12,8 | 84 |

| 13 | 79 |

| 13,2 | 77 |

| 13,4 | 70 |

| 13,5 | |

| 13,6 | 67 |

| 13,8 | 64 |

| 14 | 63 |

| 14,2 | |

| 14,4 | 50 |

| 14,5 | |

| 14,6 | 47 |

| 14,8 | 44 |

| 15 | 40 |

| 15,2 | 38 |

| 15,4 | 37 |

| 15,5 | |

| 15,6 | 35 |

| 15,8 | 33 |

| 16 | 32 |

| 16,2 | 30 |

| 16,4 | 27 |

| 16,5 | |

| 16,6 | 26 |

| 16,8 | 23 |

| 17 | 22 |

| 17,2 | 20 |

| 17,4 | 17 |

| 17,5 | |

| 17,6 | 15 |

| 17,8 | 13 |

| 18 | 10 |

| 18,2 | 9,5 |

| 18,4 | 7 |

| 18,5 | |

| 18,6 | 4,5 |

| 18,8 | 2 |

| 19 | 0 |

To measure of the bore a set of made-on-purpose plastic checkers has been used; they are fitted to a tiny metal bar with millimetric scale, inserted in the chanter from the bottom. When the checker touches the internal surface you read the measure of the lenght on the bar. The values 8,4 – 200 means that 200 mm far from the bottom end of the chanter, the inside diameter is 8,4 mm

From Chanter Winter 2016.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!