The Bagpipe Society

English Bagpipe Music of the 17th Century

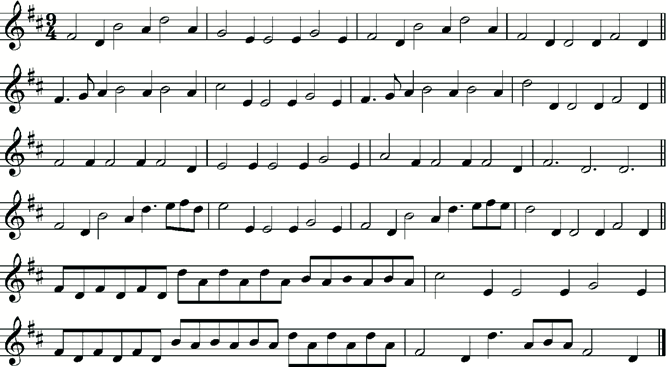

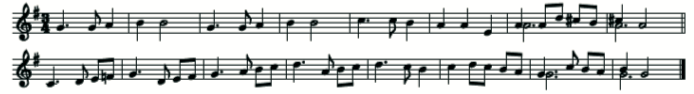

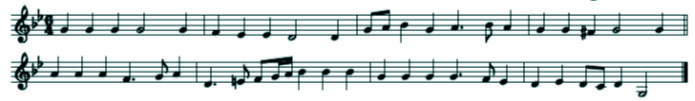

Music proclaiming itself to be for the bagpipe, either published or in manuscript, first appears in the North East of Scotland in 1717. In his seminal 1972 essay ‘English Bagpipe Music’1, Roderick Cannon introduced a resource which took researches into this topic back another 40 or 50 years, to Playford’s Musick’s Recreation on the Viol, Lyra-Way of 1661, which contained five tunes for the bass viol set up in ‘the bagpipe tuning’. Only three of these tunes, however, could be played on a nine-note chanter. I have added these three to the end of this article.

By 1994 I know that Roderick was aware of the existence of two other sources of similar nature, but with considerably more music and predating Playford by twenty or more years, but as far as I know he did not publish anything about them. I say 1994, because that was when I encountered the playing of Jordi Sovall; I had serendipitously heard an announcement of a BBC radio broadcast of the renowned viol player performing bagpipe music from a 17th century manuscript. I recorded this recital and transcribed the music. It was a moment that transformed my musical life. Since then I have published some of this music in two different contexts; here my intention is to present all eighteen pieces, together with the three that Roderick Cannon identified and two related pieces that are cited in contemporary English sources as being part of the 17th century piper’s repertoire.

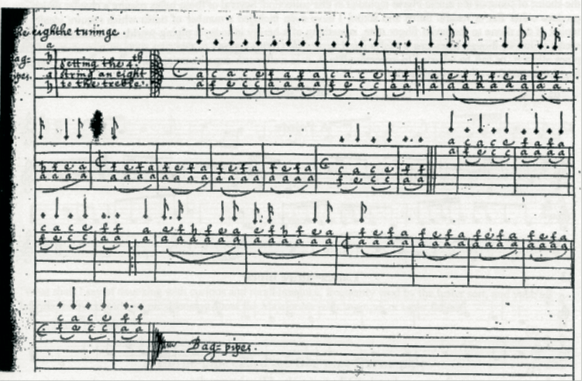

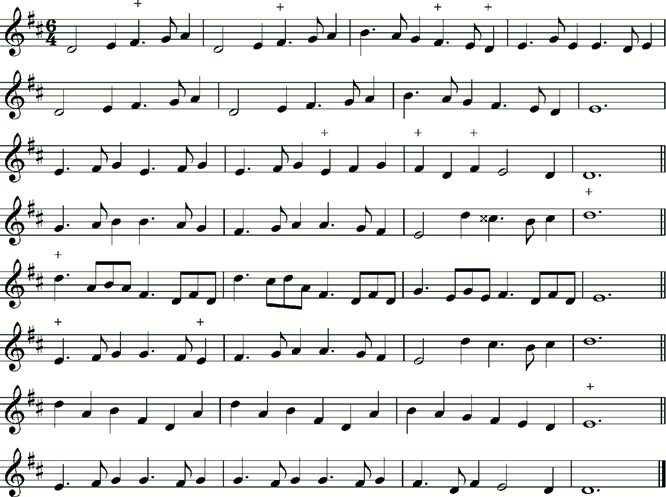

The two principle sources are manuscripts for the bass viol or viola-de gamba. The music at the top of this article is from the first of these, the anonymous manuscript now held in the Henry Watson Music Library at Manchester Public Library2; it is known accordingly as the ‘Manchester Manuscript’. It appears to date from somewhere between 1640 and 1660. The second manuscript is in the Chester Records Office3 and is the work of Sir Peter Leycester, antiquarian and Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire. His work is in the form of ‘A Booke of Lessons for the Lyra=viole’ and carries the date 1659. These manuscripts come from an area of the North-West of England well-known for its historical links with bagpiping and their compilers may have been known to each other.

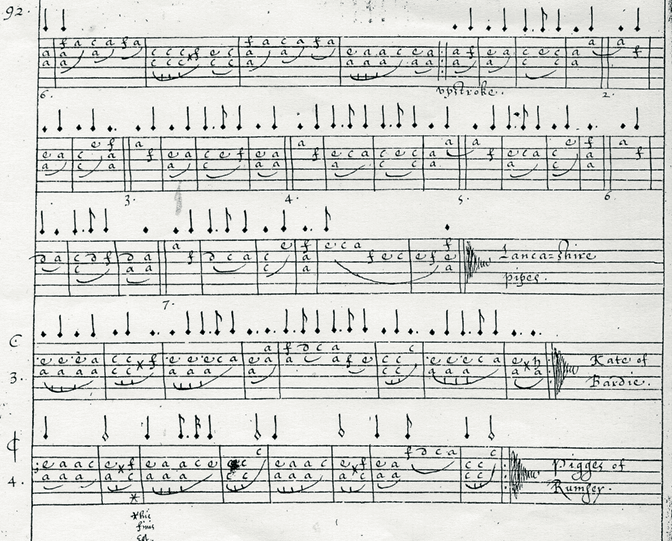

What makes these manuscripts of immense value to bagpipers interested in early sources of pipe music is that they are both divided into sections categorised by the manner in which the viol is tuned. The bass viol is a fretted instrument with six strings which can be set in a variety of tunings; the Leycester manuscript has one tuning labeled ‘Bagge=pipe way’ and this section contains eight tunes plus what looks like a brief exercise. The Manchester manuscript has two tunings, one labeled ‘lancashire pipes’ (‘the seventh tuninge’‘) and the other ‘Bag=pipes’ (‘the eighthe tuninge’) which between them contain eight tunes, including one titled ‘bag=pipes’ and another ‘Lanca=shire pipes’. All the melodic music in these sections of both manuscripts stays within the nine-note range; a good deal of it is Scottish music, and some of these tunes were popular enough to appear in several manuscripts, for various instruments, from the period around the beginning of the 17th century.

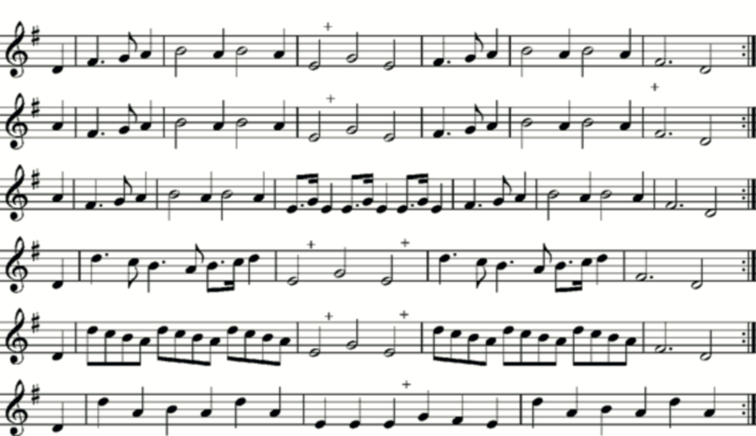

The music for ‘Lancashire Pipes’ and the remainder of the bagpipe music in the Manchester MS was printed in my Robin with the Bagpipe.4\ Of the music in the Leycester MS, the jigge, the hornpipe, the Canaries and the Hunts Up, were transcribed in The Day it Daws; the other tunes were published for the first time in Common Stock, the journal of The Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society5. The Leycester MS ‘horne=pipe’, first published by John Ward in his seminal essay ‘The Lancashire Hornpipe’6 is clearly the Manchester Manuscript’s ‘Lancashire pipes’ material in a different working. It is titled ‘A Horne=pipe called the Bag=pipe Horne=pipe other=wise The Knave of Clubs’. Both these pieces conclude with an ‘Upstroke’, that in the Leycester MS being titled ‘Upstroke to be played after the hornpipe’, the content of which is quite different to that of the Manchester MS. Whatever these manuscripts meant by the term ‘Upstroke’ it is intriguing to note that the word appears in an identical context in a contemporary poem written by William Blundell of Crosby, Lancashire, a noted cavalier and Royalist [as indeed was Leycester and, it seems, most of the known musicians of the period ]. The poem is titled ‘A country song remembering the harmless mirth of Lancashire in peaceable times, to the tune of Roger o’ Coverley’.7 It describes a country fair to which come ‘the lads’ from surrounding villages who engage in a competition of hornpipe dancing, each to the sound of their bagpiper’s music. In addition to naming two pipers and several dance tunes of the period, the poem, the main part of which is in 9/4 rhythm, finishes with a section set to ‘the Upstroke’, in 6/4. This poem is also a source of two other tunes named as being played by the piper for the lads to dance to, and I have appended an excerpt from the poem and the music for these at the end of this article.

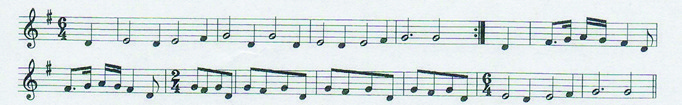

Fig. 2 is a transcription of the tablature in Fig. 1; ‘Bag=pipes’ from the ‘eighthe tuninge’; the entire piece here is repeated in the manuscript an octave higher; both times are accompanied by a drone a fifth below (G). This is different to the tuning Playford uses as his ‘Bag-pipe tuning. Here, the third string appears not to be played, the fourth and fifth strings tuned an octave below the first and second.

(Image provided by kind permission of the Henry Watson Music Library, Manchester Library and Information Service)

The remainder of the tunes in the Manchester manuscript come from the section of labelled ‘The seventh tuninge Lanca=shire pipes’, essentially the same as Playford’s. The manuscript has a ‘ninth tuninge’ labelled ‘Horn=pipe’, but the single tune given, though of interest as a hornpipe, spans an octave and a fifth and is not included here.

Editor’s Note: Sadly, due to the large number of musical examples in Pete’s article, it has not been possible to print them all in this edition. However, in consultation with Pete, I have included a selection of key pieces in order to whet your appetite. The complete article, with all the music, is available to Society members on the website and can be downloaded as a pdf.

APPENDIX

A remarkable ‘song’ is preserved in the note-book of William Blundell of Crosby in Lancashire. It is ascribed with the date 1641, and titled ‘A country song remembering the harmless mirth of Lancashire in peaceable times; to the tune of ‘Roger o’ Coverley’. It describes how six couples ‘Tired out the bagpipe and fiddle with dancing the hornpipe and diddle’. To this gathering are added ‘the lads’ from several of the surrounding villages;

‘The lads of Chowbent were there

And had brought their dogs to the bear

But they had no time to play They danced away the day

For thither then they had brought Knex10

To play Chowbent hornpipe, that Nick’s

Tommy’s and Geffrey’s shoon

Were worn quite through to the tune’

By good fortune a tune called ‘Chow Bente’ survives in two lute manuscripts from the period. This one (Fig. 22) is extracted from the tablature in Jane Pickering’s lute book (which carries the date 1616 though some of it may date from 1630-1650). The lute setting ranges widely over two and a half octaves, but the tune seems to be (as Ward suggested) a form of the ‘English Hunt’s Up’ (see Ward, 1979). I have included the closing cadence which is not strictly part of the tune but which displays the rhythmic concept. The tune also seems to be required for a ballad in a play performed in 1639 to the words ‘the great Choe bente/the little Choe bente/ Sir Piercy leigh under the line/ God bless the good Earl of Shrewsbury/ for he’s a good friend of mine” (Ward, 1979). It is a ‘galliard’ of the simplest type, which Arbeau calls ‘tourdion’. Here we have the familiar 16th century hornpipe rhythm, which Hawkins described as six crotchets, ‘four with a down, two with an up hand’ (see above), and which is clearly related to the Galliard’s four steps and a pause. However, Blundell’s poem has more to tell us:

“The Lads of Latham did dance

Their Lord Strange hornpipe, which once

Was held to have been the best

But now they do hold it too sober

And therefore will needs give it over

They call on their piper then jovially

‘Play us brave Roger o’ Coverley’.

This tune must be the ‘Lord Strange’s Galliard’ (Fig. 23) that appears in two different versions in lute books from the 1590’s. In a review of my Three Extraordinary Collections in which this tune and poem were published, it was suggested that the tune Blundell mentions should be the Lord Strange’s Hornpipe that appears in a manuscript from the north-west of England and which is the same as that in Thomas Marsden’s 1705 collection entitled ‘Lon Sclater’. I remain convinced that the galliard is indeed the tune that was rejected in 1640 as being ‘too sober’, a term which implies a bygone age; Marsden’s ‘Lon Sclater’ is no more ‘sober’ than any other in his collection.** **

Cannon, R. D., ‘English Bagpipe Music’, first published in Folk Music Journal, Vol. 2, No. 3 (EFDSS, 1972). Reprinted in Essays on The Bagpipe in England Its History, Music and Iconography, Ed Stewart, P., (Bagpipe Society, 2014)

2 The complete contents of the ‘Manchester Manuscript’ were published by Peacock Press, 2003 as The Manchester Gamba Book. Containing 246 items, it is the largest known manuscript collection for the instrument. The majority of the contents are sarabandes, corantos, almains, preludes etc.

3 A Booke of Lessons for the Lyro=Viole, Chester Records Office, GB-CHEr DLT/B 31

4 Stewart, P., Robin with the Bagpipe, White House Tune Books, 2001

5 ‘The Bagge-pipe Way’, Common Stock, June 2011

6 Ward, John M., ‘The Lancashire Hornpipe’, in Essays in Musicology - A Tribute to Alvin Johnson, A.M.S., 1990 pp. 140-173. Online (21/04/2016) at http://tinyurl.com/jbozjt5

7 Blundell’s poem was published in Crosby Records: A Cavalier’s Notebook, by Rev. T Ellison Gibson; available on line, p.234https://archive.org/details/crosbyrecordscav00blunuoft. [retrieved 21/04/2016]

8 For other settings of ‘Hunts Up’ and the Canaries see Stewart, P., The Day it Daws, White House Tune Books, 2005. The ‘Scottish Jygge’ also appears, along with a Hunts Up, copied in a rather illiterate hand into the ‘Tokyo copy’ of Thomas Robinson’s New Lessons for the Cithern, 1609, available online at http://nanki-ml.dmc.keio.ac.jp/M-06_072_R044/content/0008_large.html.

9 Reprinted in Essays on The Bagpipe in England, Its History, Music and Iconography, The Bagpipe Society, 2014

10 Gibson, who edited the notebook in 1880, says ‘Thomas Knex was a noted piper’.

Fig. 17 ‘A Health to All the Lords and Ladies of the Court’ The remaining tunes in this collection of ‘bagpipe’ music is something quite different; it has the feeling of a dance from the Playford collections (the first of which was published in 1651, when the Leycester MS was still being prepared). Although Playford published a good deal of Scottish music, this is most likely an English song. Its first two bars are derived from Praetorius’ ‘La Bourré’>

Download Full article

Download the PDF of [the full article](https://archive.bagpipesociety.org.uk/pdf/chanter-2016-autumn-extra-English Bagpipe Music of the 17th century.pdf) with full musical examples.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!