The Bagpipe Society

The Estonian Bagpipe - Torupill

Compiled by Catlin Magi and edited by Jane Moulder

The Estonian bagpipe is called a torupill, with toru meaning pipe and pill being a general term for a musical instrument. In fact, sometimes the instrument is simply referred to as a pill. The first mention we have of the bagpipe dates back to the 16th century when, in describing a peasant’s uprising in 1560, Johannes Renner refers to a bagpiper riding on horseback in front of the rebel’s leader. There is another reference in 1584 in the Livonian Chronicle where it mentions village festivities and the fact that large bagpipes were well-known in the many villages near Tallin. Sadly, there isn’t enough information to say exactly when the bagpipe became widespread in Estonia but some say that it may have been introduced by the Germans. However, analysis of the bagpipe tunes from west and north Estonia shows a strong Swedish influence.

The instrument became popular all over Estonia but, along with other folk music, the tradition lasted longest in the west and north of Estonia. The bagpipe was played for dancing and the bagpiper was an essential figure at weddings and many other significant occasions. According to some sources, bagpipe players were sometimes exempted from working for the lords of the manor but they had to take part and play at what were called “bagpipe days”. In order to make people work more productively, a bagpipe player was brought to the fields, where he followed the harvesters all day playing the torupill. If he noticed that someone was slowing down or was not doing the job properly, he stood next to the person and produced sounds with his instrument resembling the screams of a pig which had gotten stuck somewhere! This would at once attract attention and laughter from other workers on the field.

In Estonia, the bagpiper was an essential addition at dances and social gatherings. No pub could manage without a good musician! Some old ceremonial dances, such as the Round Dance (Voortants) and the Tail Dance (Sabatants) were performed together with a bagpiper who would lead the dance by walking in front of everyone else. Literary sources indicate that by the 17th century, ceremonial music was an important part of the bagpipers’ repertoire and the presence of a bagpiper was very important during weddings with special tunes, marches or riding songs being played during the wedding procession.

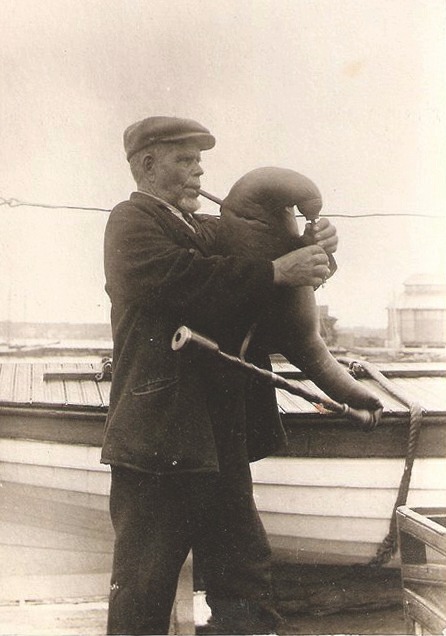

The popularity of the bagpipe started to fade in Estonia at the beginning of 19th century and the tradition died out in many places until only a few old people who had seen and heard a bagpipe player were left. However, there were still a few players left on the coastal area and fortunately some of their work has been recorded. The amount of recordings of old authentic bagpipe tunes in Estonia is remarkable in Northern Europe – the Estonian Folklore Archive holds around a hundred bagpipe tunes played by eight players which were recorded between 1913- 1956.

Estonian bagpipe tunes can be quite long with 3 or more sections but their structure remains simple. The songs usually consist of repetitions and variations of one phrase, alternating quite freely, without pertaining to a certain form. The melody is mostly based on major scale. Often triads can be heard, but there is no functional harmonious base in such tunes.

Characteristic of many bagpipe tunes is their original three-part metro rhythm. Many bagpipe tunes were eventually taken over by fiddlers, accordionists and kannel players (an Estonian zither-like instrument).

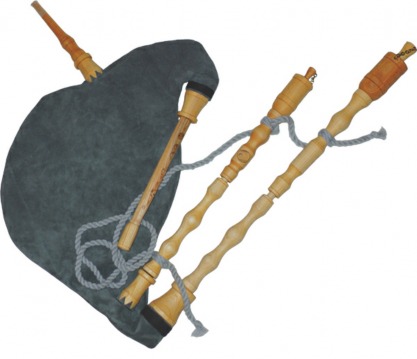

The parts of the Torupill

In the west and north of Estonia, and also on the surrounding islands, the bag was traditionally made of the maw or stomach of a grey seal. A bagpiper from the Hiiu island is known to have said that when his bagpipe got wet, it sounded richer because the seal is a sea animal! However, bags were also made of the maw or skin of ox, cows, elks as well as dogs. There were even records of Lynx being used and when made into the instrument, it still retained the head and legs.

The chanter was traditionally made of juniper, pine, ash or, in rare cases, a tube of cane. The chanter bores were cylindrical but the outside could be slightly conical in shape. The chanters had 5 - 7 holes which could be round or oval and they had single cane reeds. More rarely, a goose quill was used for a reed.

The drones could vary in shape and diameter. The length of the pipes were dependent on how many drones were used – a single drone would be quite long, and if two drones were used, they were shorter. In some rare cases bagpipes with 3 drones could be found. The reed is similar to that of the chanter, a single reed but somewhat larger. The drones were tuned an octave or a fifth below the chanter key-note.

The revival of the torupill

The last traditional bagpiper, Aleksander Maaker, died in 1968. Bagpipe playing could easily have died out at that point but in 1970, Olev Roomet, who was a singer but with a great interest in the pipes, decided to do something about it. Olev had some knowledge of the pipes and could play them as he had met with and learned some piping techniques from some of the old players. Using his knowledge, he decided to revive the tradition by training 25 new players so they could take part in the annual traditional Dance Festival. Together with Voldemar Süda, a well-known musical instrument maker, they made 25 bagpipes based on some of the surviving original instruments. Performing with the pipes at this festival marked the start of the revival of the Estonian bagpipe playing tradition.

Instrument makers

In the same way that the tradition of bagpipe playing died out for a while, similarly, there was a break in the tradition of making bagpipes. Unfortunately, nothing is known about the old bagpipe makers but it was likely that the players also made their own instruments.

After becoming inspired by the Dance Festival in 1970, Johannes and Ants Taul (father and son) started reviving the bagpipe making tradition based on the old bagpipes which were stored in archives. Thus, the shape and design of the bagpipes have the look of those that were used at the beginning of 19th century.

Now Ants’s son, Andrus, has taken on the skills of his father and is the foremost maker of the torupill. There have been makers, such as Tarmo Kivisilla. Tarmo has also helped to pass his skills to others and in 2004 he held an instrument making workshop where he taught about 10 people to make their own bagpipe.

Today’s Musicians

Since the revival started in the 1970s a number of different bagpipe groups and players have emerged. The repertoire has mainly been the popular traditional tunes which used to be played by the village bands.

At the beginning of 1990s, Estonian music students started to revive the old music and instrument traditions using the model which had been employed, with great success, in Scandinavian music schools. The Viljandi Culture Academy under the guidance of Ando Kiviberg was instrumental in this and students were able to learn tunes from archive recordings so that they could imitate the style and techniques of the old players.

The Estonian bagpipe has now been taken to another level by younger players, such as myself Sandra Sillamaa and Juhan Suits, who had all studied at the Viljandi Culture Academy.

The torupill is now being played by a number of people and the instrument is slowly becoming more popular since there are bagpipe courses being run outside of the university system. There are two bagpipe festivals in Estonia which have helped to promote both traditional music and the torupil: the Hanseatic Days festival at Viljandi and the Lahemaa Bagpipe Festival at Palmse Manor. The Lahemaa festival was started by the Ants Taul and takes place every two years in August. The Estonian northern coast, where the festival is based, has always been an area with rich bagpipe traditions. Four traditional bagpipe players - Jakob Kilström, Tõnu Eslon, Peeter Piilpärk and Jakob Ratsov- grew up in that area and their tunes can be heard on the archival recordings dating back to 1913-1936. The festival has done much to preserve local bagpipe tunes and introduce them to new players. At the “Torupill ja teine“ which is part of the Hanseatic Days event, different instruments were introduced, such as the fiddle, bowed harp and Jew’s harp, to play along with the torupill. This has had the result of enriching the bagpipe repertoire with traditional music of the other instruments.

The tradition continues to grow!

Cätlin is part of a trio called the Torupilli-Jussi Trio and they have just released their first cd. Listen to them on Soundcloud at https://soundcloud.com/torupilli- jussi-trio. Cätlin is also the subject of Andy Letcher’s In the Bag later in the journal.

Overleaf is the notation for a traditional Estonian tune. You can hear it being played by Troupilli-Jussi Trio at http://tinyurl.com/m93orbe Also on the website (http://www.folk.ee/) you can find other Estonian tunes with their audio/video recordings (click on the tab marked “lood” = compositions) as well as archive recordings of the traditional players.

By Mägi, Cätlin Sillamaa, Sandra Trad

From Chanter Summer 2015.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!